The Lost Knowledge of the Ancients: Were Humans the First? Part III

This series has highlighted many real modern world phenomena that don’t quite fit the conventional wisdom regarding the ancient history of the world as we think we know it. In this concluding section, we will look at anomalies in skulls and some unexplained early metallurgy.

Suspicious Skulls

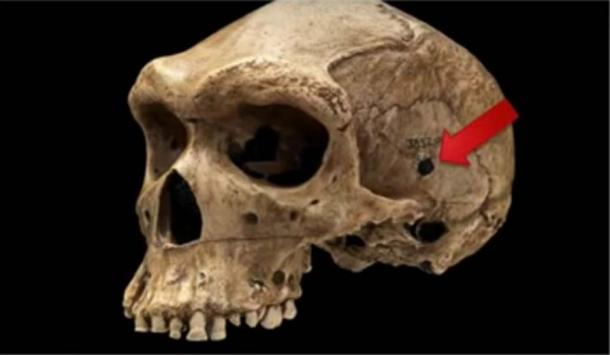

On the ground floor of the Museum of Natural History in London, a human skull is displayed. It comes from a cavern in Northern Rhodesia, and has a perfectly round hole on the left side. There are no radical cracks which are usually present if an injury is caused by a cold weapon. The right side of the skull is shattered. The skulls of soldiers killed by rifle bullets have identical appearance. The cranium is identified as belonging to a man who lived over 40,000 years ago at a time when no guns were made. An arrow could not have produced such a perfectly round hole on the left side of the skull and shattered the right side as well. Either there is something wrong with the dating of the skull, or the origin of the hole remains a mystery.

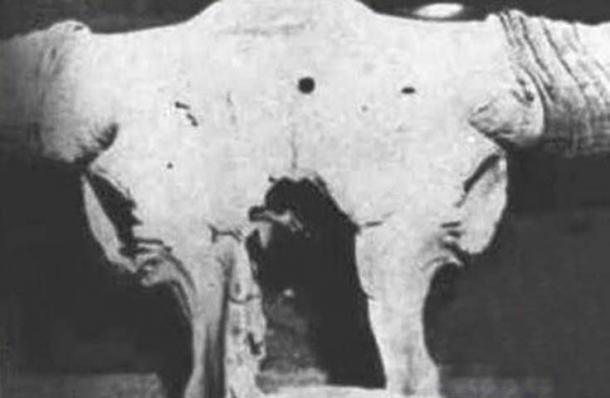

The Paleontological Museum of Russia has a skull of an auroch which is supposed to be hundreds of thousands of years old. It shows a clear round hole on its frontal part and scientific evidence has proven that although the skull was pierced, the brain was not injured and the beast’s wound healed. In that distant past, apeman was supposedly armed only with clubs. The perfectly round hole without radial lines looks very much like one made by a bullet. The question is – who shot the auroch?

Enigmatic Meteorite

A meteorite of an unusual shape found near Eaton, Colorado, created a riddle. An analysis by an American expert on meteorics, H. H. Nininger, indicated that the meteorite was composed of an alloy of copper, lead and zinc, that is brass, which does not exist in nature. The meteorite could not have been “Space garbage” because it fell in 1931.

Iron Nails from Antiquity?

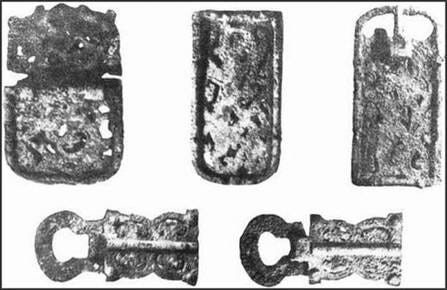

In the 16th century the Spanish conquistadors came across an 18-centimetre iron nail solidly incrusted in rock in a Peruvian mine. The rock was estimated to be tens of thousands of years old. Since iron was unknown to the American Indian until the Conquest, one wonders whose nail it was. The Spanish Viceroy Don Franciso de Toledo kept the mysterious nail in his study as a souvenir.

According to the London Times of December 24, 1851 a Mr. Hiram de Witt found a piece of auriferous quartz in California. When he dropped it accidentally, an iron nail with a perfect head was found to be inside the quartz. About the same time Sir David Brewster made a report to the British Association for the Advancement of Science which created a sensation. A block of stone from Kin-goodie Quarry in north Britain contained a nail, the end of which was corroded. But at least an inch of it, including the head, lay embedded in the rock. Because of the great age of the geological strata where these three iron nails were found, the identity of their makers remains a mystery.

Steel Cube in Coal Conundrum

In 1885 in the foundry of Isidor Braun of Vöcklabruck, Austria, a block of coal was broken and a small steel cube, 67 mm x 47 mm fell out. A deep incision ran around it and the edges were rounded on two faces. Only human hands could have made these.

The son of Braun took the article to the Linz Museum but in the course of decades it was lost. However, a cast of the cube has been kept by the Linz Museum. Contemporary magazines such as Nature (London, November 1886) or L´Astronomie (paris, 1887) had articles about this strange find. Some scientists endeavored to explain it as a meteorite from the Tertiary coal period. Others wanted an explanation for the groove around the cube, its perfect form and the origin. Some explain this as some cast iron used in mining machinery as ballast. The debate has never been closed.

The Four (or more) Ages of Man

Greek myths speak of four ages of man – first came the Golden Age, followed by the Silver Age, after which arrived the Bronze Age. The last epoch is the Iron Age - in which we live today.

Though iron is more plentiful than copper or gold, it is more difficult to melt and forge. Thus, the ancient Greeks told us about the progress of metallurgy by this simple tale of how it had started with soft metals and ended with hard iron.

The Stone Age, which lasted for a long time, was followed by the Chalcolithic Age; when old perfected stone implements were mainly used, but copper tools and weapons were also making their appearance as luxuries.

Then came bronze, a hard alloy made of copper with the addition of one-tenth of tin. The Third Millennium BC in Sumeria and Egypt is predominantly the Copper and Bronze Age. No clear picture is available of where and how bronze first appeared. To combine copper which came from Sinai, Canaan, Crete, Cyprus, Portugal, or other parts of the Mediterranean, with rare tin from Etruria, Gaul, Spain, Cornwall, and Bohemia, it would have been necessary to have organized transport, skilled labor, and furnaces with temperatures well over 1000 degrees Celsius. (1832 degrees Fahrenheit)

Bronze, a mixture of copper and tin, is strong and durable. It should have taken ages to discover that the addition of one-tenth of tin to copper creates a better metal. Yet strangely enough, copper artifacts in our museums are few. Bronze seems to have appeared suddenly and spread far and wide in great profusion. The similarity of bronze artifacts found in different parts of Europe compels us to conclude that they came from one manufacturing center or school of technology. The alloy appears quite suddenly. Was the discovery made by experimentation or chance?

South American Metallurgy

The discovery of bronze was not simultaneous in the Old World and the New. Copper, which is a component of bronze, was mined in Mesopotamia about 3500 BC, but not before 2000 BC in Peru (iron was unknown to the Incas until after the arrival of Pizzaro.)

Certain achievements of the South American indigenous people in metallurgy are enigmatic. Ornaments of platinum were found in Ecuador. This poses a provoking question-how could the American Indian produce the temperature of over 1770 degrees Celsius (3218 degrees Fahrenheit) necessary to melt it? It should be noted here that the melting of platinum in Europe was achieved only two centuries ago.

In testing an alloy from the prehistoric artifact, the United States Bureau of Standards ascertained that the original dwellers of America had furnaces capable of producing a temperature of 9000 degrees Celsius (16232 degrees Fahrenheit) seven thousand years ago. No satisfactory explanation has been given yet as to how such a technical feat was possible at so remote a date as 5000 BC.

Other Mysterious Metal Artifacts

The tomb of Chinese general Chow Chu (265-316 AD) also presents a mystery. When analyzed by a spectroscope, a metal girdle showed 10% copper, 5% manganese, and 85% aluminum. But according to the history of science, aluminum was obtained for the first time by Oerstead in 1825 by a chemical method. To satisfy industrial demands, electrolysis was later introduced into the manufacturing process. Needless to say, an ornament made of aluminum, whether chemically or electrolytically produced, seems out of place in a 3rd century grave in China. It is hardly reasonable to think that this aluminum artifact was the only one manufactured in China.

The Kutb (Qutb) Minar iron pillar in Delhi weighs 6 tons and is about 7.5 meters (24.6 ft.) high. For fifteen centuries, it has withstood the tropical sunshine of India plus the heavy downpours during monsoons. Yet it does not show any signs of rust formation and provides proof of superior metallurgical skill in ancient India. Aside from the mystery of the non-corrosive metal of which the column is made, the task of forging so large a pillar could not have been easily achieved without our high technology - which is why it is surprising to find such an achievement in the year 415 AD.

The pillar stands as a mute witness to the scientific tradition preserved by the people of antiquity in all parts of the world. Men whom time has forgotten held the answers to these riddles of the history of science.

Conclusions from the Anomalies

These examples may not be solid proof of previous advanced knowledge but along with the other examples given previously certainly present us with the possibility. The perplexities cannot be cleared up unless an open-minded reappraisal of prehistory is made. The evidence assembled here points to the existence of a certain level of technology at what we imagined to be the dawn of mankind.

Two theories might help explain all the anomalies described in this article series – either there was some kind of technological civilization in a bygone past, or the Earth has been visited by beings from other stellar worlds or dimensions with such technical capabilities.

Lost Knowledge of the Ancients Part I

Lost Knowledge of the Ancients Part II

Top image: Clockwise: Rhodesia Man (YouTube Screenshot), H. H. Nininger (Fair Use), Auroch skull (Technology of the Gods: The Incredible Sciences of the Ancients), Salzburg Cube (Public Domain),Roman Nails (CC BY-SA 2.0)

By Sam Bostrom

Thank you. I’ve been wondering about the origins of alloy metals and ceramics.

Absolutely fascinating to read this thank you so much for such a great article.