The Elasmotherium, colloquially known as the Giant Rhinoceros or the Giant Siberian Unicorn, is a prehistoric rhinoceros species that once roamed the Eurasian region during the Late Pliocene and Pleistocene eras. Their existence has been traced back to 2.6 million years ago, with the most recent fossils being approximately 29,000 years old. The most recognized species of this group, the E. sibiricum, compared to a mammoth in size, had a hairy exterior and is believed to have sported a large horn on its forehead, giving rise to its nickname, the "Siberian Unicorn". Initial descriptions estimate the beast to have stood around 2 meters (6.56 ft.) in height, measured 4.5 meters (14.76 ft.) in length, and weighed a hefty 4 tonnes.

Decoding the Tale of the Siberian Unicorn

The Elasmotherium species was first identified in 1808 by Johan Fischer von Waldheim, the perpetual Director of the Natural History Museum at Moscow University. His claim was based solely on the lower jaw of the species, gifted to the museum by Yekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova-Dashkova, which led to further study and identification of the species.

In March 2016, an excellently preserved skull was discovered in the Pavlodar region of Kazakhstan, indicating the species' survival until the Pleistocene era around 29,000 years ago, challenging the prior belief that they had vanished 350,000 years ago. Judging by the skull's size and condition, it is hypothesized that it belonged to an elderly male, though the cause of death remains a mystery.

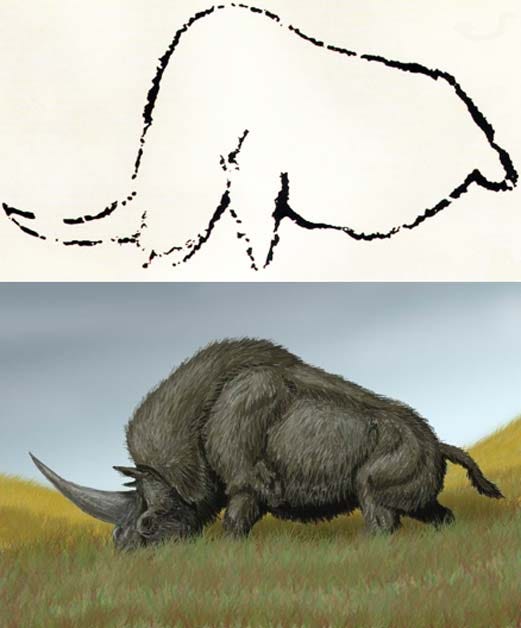

The Siberian unicorn's appearance, dietary habits, and behavior are subjects of various hypotheses owing to the wide-ranging interpretations of the reconstructions. Some depict the creature running like a horse, others bent over with its head towards the ground similar to a bison, and still others submerged in a swamp like a hippo.

Controversies over the Siberian Unicorn’s Horn and Extinction

The existence, size, and purpose of the horn remain hotly contested. Speculations regarding its function span from self-defense, to mate attraction, to competition deterrence, to snow clearing for feeding, and even to digging for water and plant roots. Considering the creatures were herbivores like present-day rhinos, it's unlikely the horn was used to attack or kill prey.

Only indirect evidence from sparse specimens exists to confirm if the beast had a horn or not and whether it was covered in hair or was hairless. Nonetheless, some evidence points towards the animal having a hairy exterior, much like the well-known woolly mammoth.

The primary evidence indicating that the Siberian unicorn possessed a horn is the frontal protrusion on the skull, which caught 19th-century paleontologists' attention and was instantly deemed the base for a horn. There is also evidence that the horn was not circular, as a fossil with a non-circular, partially healed puncture wound in the base suggests it could have been the result of combat with another male possessing a horn.

While male Siberian unicorns likely engaged in territorial disputes, their territory stretched from the Don River to eastern Kazakhstan. Findings suggest these ancient rhinos inhabited the southeast of the West Siberian Plain for an extended period. The exact cause of the extinction of the last Siberian unicorns remains uncertain. Scientists are examining specific environmental elements that might have triggered the species' extinction, hoping to glean insights that could be applied to modern species facing extinction.

The Legendary Unicorn

Myths and legends about unicorns, or creatures with a single horn, have permeated Chinese and Eastern European cultures for thousands of years. The Chinese term "K’i-lin," referring to a certain type of creature, was assimilated into Turkish and Mongolic languages and folklore. Although scribes in these languages struggled to describe the creature, a recurring theme was its single horn and its imposing size.

A bronze relic from the Warring States period portrays an animal remarkably similar to one depicted in cave paintings thought to represent Elasmotherium: grazing with its head lowered, a horn jutting from its forehead, and a drooping head and shoulders.

In 1866, Vasily Radlov encountered a Yakut legend in Siberia about a "gigantic black bull" slain by a lone spear. The beast reportedly had a single horn so enormous it had to be transported by sled. Other legends in this region typically involve a large white or blue woolly bull with a massive horn on its forehead.

From medieval Northern Russia, a collection of ballads, named "Golubinaia kniga" or "The Book of the Dove," influenced by Zoroastrianism and laced with Christian nuances, emerged. The ballads portray a righteous unicorn combating a lion, symbolizing falsehoods. The unicorn in these tales resided on a sacred mountain and was considered the progenitor of all animals. This creature saved the world from drought by using its horn to dig up springs of clean, fresh water. At night, it wandered the plains, blazing trails with its mighty horn.

This creature features in other religious scriptures as well, though it is generally seen more as a symbolic entity than a real one. The Arabo-Persian term for a unicorn conflates unicorn and rhinoceros, viewing the rhinoceros as a symbol of truth and goodness. In Christianity, the single horn represents monotheism.

While mythology hints at the creature's existence, it is only circumstantial evidence. More research and additional fossils need to be discovered before we can definitively determine what this creature looked like and if unicorns were ever real.

If you're intrigued by our deep dives into the mysteries of history and want access to even more exclusive content, consider subscribing to Ancient Origins Premium.

Top Image: A reconstruction of what the Siberian unicorn may have looked like. Source: Elenarts /Adobe Stock

Yet another clear indication that Earth benefitted from low gravity until maybe 10.000 years ago. The loss of these creatures and the mammoths is not a coincidence. The Saturnian theory suggests we had a brown dwarf star until very recently! The transition to our current G2 Sol was catastrophic and wiped out all the old species, along with many humans not underground or in caves.