The Radhanites: A Glimpse into the Trade Networks of the Middle Ages

It is no secret that throughout the classical and early medieval period, trade played an immense role in the economy of the world. Trade routes were spread all over Eurasia, and effectively connected western and eastern societies. The aristocracy enjoyed the commodities, precious goods were highly priced, and certain nations thrived as a result. Amongst the chief, if not the only, traders of that period were the Radhanite Jews. The Radhanites dominated the Eurasian trade routes, as noted in numerous historical sources. Dealing with a variety of goods, they managed to control much of the economic development and influences in early medieval societies. But who exactly were these Radhanites, and what was their goal? Join us as we retrace the steps of these traders and revisit some of the earliest geographical and travel accounts, in the hopes of shedding some much needed light on the mid- medieval trade networks .

The Earliest Accounts of the Radhanites and Their Trade Routes

The Radhanites were well known in the early medieval period under a variety of names. Most of what we know today about them comes from Islamic sources. Of course, it is no secret that early Islamic Caliphates of the period boasted some of the finest and, perhaps, the only travelers and geographers who left striking accounts of the world during that period. In their sources, the Radhanites were known as الرذنية - ar-Raðaniyya, or in Hebrew as רדהנים - Radhanim. The exact origins of this name are not precisely known, but most scholars and etymologists agree that the word is of Persian origin, a name given by the Islamic travelers to these Jewish traders. It comes from the words rah (way, path) and dān ( one who knows), meaning “those who know the paths,” something rather sensible as a name for the traders.

Another plausible theory that connects to this term, is the Radhanite place of origin. Several key sources place their point of emergence in the Rhone Valley in France. In Latin, this river is known as Rhodanus, or Rhodanos, in Greek. Thus, the Radhanites would likely be named by the area from which they came, the valley of the Rhone, as they were also known as “French Jews”. Then again, some sources name their place of origin in the historical province of Radhan, near modern Baghdad - which remains the least likely option.

Fresco of an Islamic Caliphate. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

One of the foremost sources on Radhanite Jews is from an early Islamic geographer and traveler, Abu'l-Qasim Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Khordadbeh (ابوالقاسم عبیدالله ابن خرداذبه), who lived from roughly 820 to 912 AD, and is most commonly known as Ibn Khordadbeh. He is well known for his major work, called the Kitāb al-Masālik w’al- Mamālik ( كتاب المسالك والممالك), known today as the “Book of Roads and Kingdoms”. This work deals primarily with the various peoples that inhabited or were common in the Abbasid Caliphate, and precisely details all the important trade routes that passed through what was then known as the “ Muslim World ”. Today, this historical source is one of the last remaining sources that go into detail about the Radhanite Jews, and thus one of the more important when it comes to medieval trade networks.

Early Trade Routes between Europe and Asia. ( Public Domain )

In his work, Ibn Khordadbeh mentions all the stations and cities that were visited on the path of the Radhanite traders. He begins his account by stating that, “these Radhanite Jewish merchants,” were multilingual. They were fluent in a variety of major languages of the time, including Persian, Arabic, Greek ( rumiyya), Andalusic, Slavic ( saqlabiyya), and Frankish ( ifranjiyya). He then states that they travel both from east to west and from west to east, both by land and the sea, and that they bring with them many spices, swords, furs, embroidered cloths, sable ( sammur), and skins of beavers ( khazz). They also transported slaves, concubines, eunuchs, and other servants.

Across the Known World

Ibn Khordadbeh states that they started out from Firanja ( France) and set sail on the Western Sea ( Mediterranean). From there they travelled to al-Farama ( Pelusium), an important city on the Nile delta . From there they took their goods by land, all the way to al-Qulzum (Suez), from where they once more set sail, this time on the Eastern Sea (the Red Sea). From there they travelled to al-Jar (Medina) and al-Jeddah (Jeddah), and further east to al-Sind ( Pakistan), al-Hind (India), and al-Sin (China). From China they brought back precious spices and exotic goods: camphor, aloe wood, cinnamon, musk, and many others. From here they often took different routes. At times they would travel to Constantinople and trade with the Byzantines, or they would go to Antioch, or to the King of the Franks, or to modern day Iraq and Baghdad.

Sometimes the Radhanites would travel from France to Spain, and from there to Morocco, Tangier, Tunisia, Egypt, and modern day Israel, Syria, Iraq, and again to Pakistan, India, and China. In his work, Ibn Khordadbeh also describes their trades with the far reaches of the Slavic Lands ( saqaliba). He explicitly names this as the Land of the Rus’ who are (in his words) a part of the Slavs. From there the merchants acquired beaver and black fox pelts, as well as swords. Then they transported the goods south to the “Rumi Sea”, where the Lord of the Rum (Romans, i.e. Byzantines) taxed them. Then they travelled to Baghdad and further East, using their Slavic eunuch slaves as translators and mediators. They claimed to be Christians when in these lands.

The Radhanite Jewish trade routes prospered from roughly 750 to the late 800’s. Almost all key scholars agree that for more than a century, “virtually every drop of spice that entered Europe did so through the hands of the Radhanite Jews”, as they held the monopoly on spices, slaves, and luxury goods. One of the biggest sources of income for the Radhanites was mediating between East and West, between Christendom and Islam, and between the Kings, Caliphs, and Khagans, who all engaged in enslavement of tribes and peoples. Radhanite Jews came to dominate all early medieval trade routes and river systems, and gained a virtual monopoly on the transit of slaves , which they took with them throughout the world.

Radhanites transported and traded precious spices, exotic goods, and slaves in the Medieval Period ( janvier / Adobe Stock)

Peaceful Societies Targeted by Slave traders

Slave trade was a fact of life for many peoples during this time. About 10% of England's population, entered in the Domesday Book (1086), were slaves. The Slavic peoples during this period inhabited vast parts of Western and Eastern Europe. They were connected by language and culture, and spread out in many tribes. But as they were largely pastoral and peaceful societies, they presented a perfect target for the slave traders and their lands frequently raided. In the north of Europe, the Lechitic Slavic tribes of Rujani, the Obodriti, the Wilci, Sorbi, and many others suffered at the hands of the Germans and the Scandinavians. In the East, the tribes of the Rus’ - Drevlyani, Dregovichi, Vyatichi, Ilmeni, Severi, and others, were enslaved by the Khazars, Tatars, and the Golden Horde .

In Southeastern Europe, the South Slavic tribes were easily targeted through the central European river systems and the Adriatic coasts. The Serbs and their tribes of Zachumlians, Timochans, and further north, neighboring Czechs, Slovaks, and Carantanians were all enslaved. The Radhanites prized the Slavic slaves for several reasons. The young boys were used as eunuchs and employed in a variety of roles. The caliphs of the Islam world greatly relied on eunuchs. Young men were sold as mercenaries or bodyguards. Female slaves were also targeted and created a commodity of its own. Blonde and fair skinned Slavic women were highly sought after in the Islamic and Eastern world and were sold as concubines.

The Radhanites eventually focused on slave trade, creating a vast and elaborate trade network, through which they supplied many parts of Eurasia with eunuchs and concubines. Some of their biggest clients were the Islamic Caliphates of the Iberian Peninsula. The demand for Slavic slaves was so great that they became universally known as Saqaliba (صقالبة). In Arabic, the word saqaliba means simply a Slavic person.

Courtyard of the Concubines in Istanbul, Turkey ( saik20 / Adobe Stock)

The slave trade monopoly of the Radhanite Jews grew so large that it eclipsed their spice and luxury goods trade. So common were the Slavic slaves in Europe at the time, that the only known name for a slave (of any kind) was Sklave. Sklave is the Greek spelling of Slav. And thus it became that the name of the Slavs, which means “glorious ones / those who speak the same language,” became the word for slave. Today, the root of the word slave remains the same. These Radhanite traders and the needs of their customers were directly responsible for the misfortune of countless men and women, which in itself is one of the worst facets of the early medieval world.

One of the biggest obstacles for the trade routes of the Radhanites was Byzantium. The Byzantine officials were somewhat a thorn in the side of these merchants, as they imposed on them regular taxes and legislations related to commerce, as was common policy for their empire. Early on, the Radhanites avoided Byzantines altogether in order to avoid paying these taxes, but later on managed to fully bypass them by becoming or posing as protégés and nationals of the Italian city states, which were exempt from such imperial legislations.

When Salt Was Traded for Gold: The Salt Trade of West Africa that Built Kingdoms and Spread Culture

Tough Times Call For Tough Measures - The Medieval Village Hierarchy

A Millennium of Glory: The Rise and Fall of the Byzantine Empire

The Waning Influence

The influence of the Radhanite merchants began to significantly wane around the year 900 and beyond. With the fall of the Chinese Tang Dynasty in 908, and after the Rus’ conquered the city of Atil and defeated the Khazar Khaganate at about 960, their trading networks became affected, and lost some of its importance. New cities needed to become trade hubs. When Atil was no longer viable, nor the shores of the Caspian Sea, the Radhanites had to focus on major towns of Central Europe. Kiev remained one of the most important trade hubs, and a trade route developed that led from Prague through Poland to Kiev. In the Hebrew account of Rabbi Yehudah ben Meir from Mainz, we can see that the Radhanite Jews focused on Przemysl in Poland as their major trade hub.

Even so, the chaos that emerged after the fall of the Khazar Khaganate greatly disrupted known trade routes, as did the emergence of centralized Slavic nations and the Christianization of their tribes. The Turkic invasions of the Middle East further made trade difficult, as did the collapse of the Silk Road. Radhanites became ousted by rising commercial successes of Italian city states such as Genoa, Amalfi, Pisa, and Venice, which considered the Radhanite Jews as their competitors. The Radhanite Jewish trade networks were all but gone after this. Slave trade was gone with them, as was the spice trade. Their populations remained in various parts of Europe where they continued to develop new ways of exploitation, for which they were known throughout the Medieval period, the most well-known being the usury system .

Understanding the Big Picture

This study of the early medieval trade networks is an important insight into the realities of the trade routes and commodities of that time. It shows us that a group of people could dominate the entire trade monopoly of the European continent by ousting the competition and developing a tightly knit system of trade routes. When this trade focused on human lives, and the exploitation of innocents for slavery, the picture becomes more serious. All we can hope for is that such slavery and exploitation remains far, far in our past.

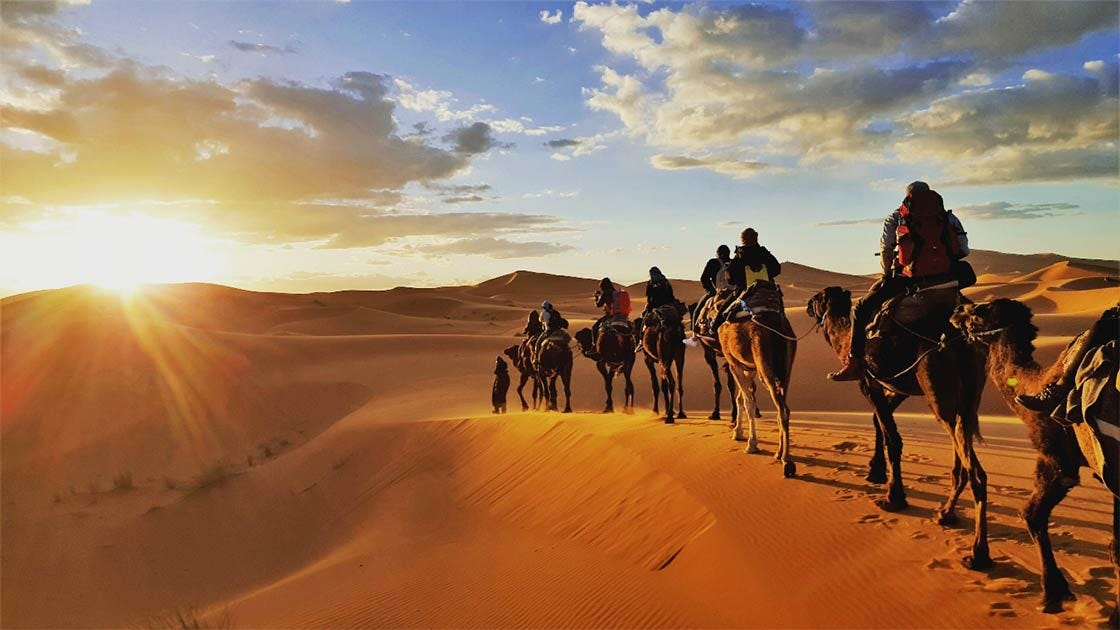

Top image: Much of the Radhanites' overland trade between Tangier and Mesopotamia was by camel. Source: Gaper / Adobe Stock

References

Brook, K. A. 2010. The Jews of Khazaria. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Cosman, P. M. and Jones, L. 2008. Handbook to Life in the Medieval World. Facts on File.

Holo, J. 2009. Byzantine Jewry in the Mediterranean Economy. Cambridge University Press.

Stillman, N. 1979. The Jews of Arab Lands - A History and Source Book. The Jewish Publication Society of America.

Suleiman, Y. 2010 . Living Islamic History: Studies in Honor of Professor Carole Hillenbrand. Edinburgh University Press.