The Measure Of Ancient Mirrors: Planispheres, Phenakistoscopes and Telescopes

In some early texts concerning long-distance viewing, the term ‘mirror’ is used, but not as a device for simple reflection. Instead, the mirror takes on other powers, and the term seems to serve as some kind of metaphor for a fantastical device to view scenes remotely.

Mirroring The Future

The Gesta Romanorum (Deeds of the Romans) is a collection of anecdotes dating from the late 13th or early 14th century. The work seems to have been written for the purpose of providing morality tales, as each anecdote or story in the text includes a heading referring to a particular moral virtue or vice — for example, de invidia. One of the tales in this book deals with the idea of viewing images at a distance in this context. A knight has married a woman who is unfaithful, but he is unaware of that fact; moreover, he is away from home, travelling in the city of Rome: “In the meantime, while the knight was passing through the main street of Rome, a wise master met him in the way, and observing him narrowly, said, “My friend, I have a secret to communicate.” “Well, master, what would you please to say?” “This day, you are one of death’s children, unless you follow my advice: your wife is a harlot, and contrives your death.” The knight, hearing what was said of his spouse, put confidence in the speaker”.

The story then turns to the device:

“Then putting into his hand a polished mirror, [the wise master] said, “Look attentively upon this, and you will see wonders.” He did so, and the meanwhile the master read to him from a book. “What see you?” he asked. “I see,” said the knight, “a certain clerk in my house.”

The story goes on to recount how the knight is able to see that this clerk has murderous intentions. When the knight returns home, his wife denies that there is anything going on, but of course, he is able to describe the events in detail, as he has seen them in the magic mirror.

Tales Of Three Brothers And A Mirror

A technical idea — however fancifully expressed it may be — is embedded in a moral narrative, a pattern that occurs a number of times in early sources that include technological devices. In fact, the idea of viewing at a distance through the use of some device is a trope found in several early tales. The Aarne-Thompson index lists a tale, traditionally labeled AT 653A, entitled The Rarest Thing in the World:

“A princess is offered to the one bringing the rarest thing in the world. Three brothers set out and acquire magic objects: a telescope which shows all that is happening in the world, a carpet (or the like) which transports one at will, and an apple (or other object) which heals or resuscitates. With the telescope it is learned that the princess is dying or dead. With the carpet they go to her immediately and with the apple they cure or restore her to life. Dispute as to who is going to marry her”.

This is known as a ‘dilemma tale’, but particularly relevant here is the interesting quest for devices, especially the odd ‘telescope’. This idea appears not only in Indo-European tales, but also in Africa. In a Wolof tale (the Wolof people are an ethnic group living in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania), the device again is used to see a girl who has died, but will be brought back to life. In another story, a magic mirror provides the three brothers with the ability to see that the chief’s daughter has passed away.

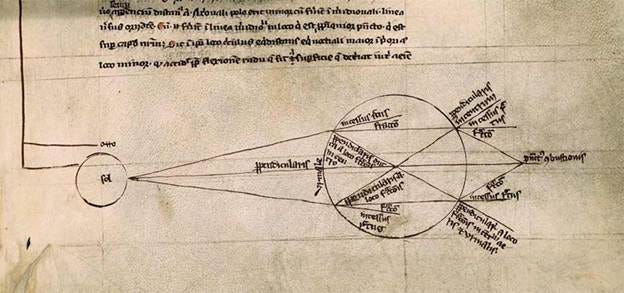

What is interesting is that this device not only allows one to see any place on the planet — it also allows the destruction of that place: “Moreover, if he be incensed against a city, and turn the face of the planisphere towards the sun’s disk, desiring to burn that city, it will be burnt”. The writer of this tale seems to have created this device from a conceptual combination of a traditional planisphere of a kind that was familiar in the Islamic world, with a magical crystal ball.

Chaucer On Astronomy

The idea of long-distance communication using a special mirror device is also found in the works of Chaucer. It is important to understand that Geoffrey Chaucer (1343 – 1400 AD) is not only famous in the world of literature, but also has been noted in the field of astronomy. Not surprisingly, then, themes related to astronomy and optics appear in his fiction. Chaucer's The Squire’s Tale recounts the arrival of a mysterious knight. This knight rides a strange brass horse, wears a magic ring that allows one to understand the speech of birds, has at his side a sword that can both wound and heal, and carries special mirror. The power of the mirror is described as follows:

This mirour eek, that I have in myn hond,

Hath swich a might, that men may in it see

Whan ther shal fallen any adversitee

Un-to your regne or to your-self also;

And openly who is your freend or foo.

And over al this, if any lady bright

Hath set hir herte on any maner wight,

If he be fals, she shal his treson see,

His newe love and al his subtiltee

So openly, that ther shal no thyng hyde.

The mirror, in short, has the ability to reveal actions happening at a distance. The device is also mentioned again a while later in the text:

And slepte hire firste sleep, and thanne awook.

For swich a joye she in hir herte took

Bothe of hire queynte [= marvelous] ring and hire mirour,

That twenty tyme she changed hir colour [= blushed];

And in hire sleep right for impressioun [because of the effect]

Of hire mirour, she hadde a visioun.

Here, the mirror also seems to have the power to cause visions in one’s sleep. Again, the descriptions are poetic, but it is important to note that the mirror itself is portrayed as being part of a set of devices — including the brass horse and the ring— that are both magical and mechanical.

16th-Century Long Distance Viewing

The story draws from many sources, and it is clear that this mirror, too, was inspired by similar accounts in other texts. There are, for example, some parallels between the description in Chaucer and the tale of the mirror in the tower from the Letter of Prester John. Writing in the same period as Chaucer, the author Jean Froissart offered a slight variant on this kind of special mirror. In his text, the mirror serves as a communication device in a very particular way: a “knight when parted from his lady puts beneath his pillow a mirror that apparently causes him to see his lady in a dream.”

The tradition in Western literature of the mirror as an object for viewing at a distance continued into the 16th century. For example, the English playwright Anthony Munday (1560? - 1633), in his play John a Kent and John a Cumber, has a magic mirror or glasse that again allows people to see others at a distance.

Phenakistoscopes: Image Transmission

An early Chinese text, the Xijing Zaji (西京雜記 Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital) describes how Emperor Gaozu (256 - 195 BC) entered the storehouse of the palace at Xianyang. At one point, the text notes that among other mechanical devices in the storehouse, there is the following item:

“There [also] was a wind instrument of jade, two chi three cun in length, with twenty-six holes. When it was played, one would see vehicles, horses, and mountain forests, one right after another. When one ceased playing [the instrument], one stopped seeing these images. [This instrument] was inscribed “jade tube of brightness and beauty”.

The meaning here is not entirely clear. Particularly curious is the phrase “one would see vehicles, horses, and mountain forests”; as the passage states, this indicates that one would see images of these things when playing the instrument. This may refer to some kind of moving magic lantern, or even a type of zoetrope or phenakistoscope. Perhaps the power of one’s breath entering into the wind instrument also provided some motive force to a wheel that had the images on it.

The phenakistoscope dates back to the beginning of the 19th century, but it is likely that an understanding of the “link between rotary motion and persistence of vision” dates from a much earlier period. Euclid (fl. 300 BC.) wrote concerning the related phenomenon of induced motion: if a series of objects move together in one direction while another object remains stationary, then the latter object ends up appearing to move in the opposite direction from the former. Lucretius, in the first century BC, seems to have understood the phenomenon of apparent motion, a fact noted by the Belgian scientist Joseph Plateau, who developed the phenakistoscope in the 19th century.

Lucretius writes as follows:

“It should be added that there is nothing remarkable in the fact that images walk and rhythmically move their arms and other limbs. It is indeed true that images seen in sleep seem to do this, and the reason for it is this: when one image fades away and is succeeded by another in a different position, it looks as though the former image has changed its posture. Of course, we must assume that this happens extremely rapidly: so immense is the velocity of the images, so immense the store of them, and so immense is the store of particles emitted at any single perceptible point of time, to ensure that the supply of images is continuous”.

It seems clear that this is an explanation of how apparent movement is caused by the succession of images. Whether this was ever put into practical use in Lucretius’ time is an open question.

Perhaps the Chinese also understood mechanical animation centuries ago, as the passage from the Xijing Zaji implies. The historical evidence certainly reveals that there were early technologies for image creation, such as shadow puppetry — which has a long history throughout Asia, from China to Java. The actual history of Chinese experimentation with shadow images is somewhat obscure. Regardless, although Chinese sources do not imply any transmission of images, they indicate an understanding of mechanical devices that could create images. To be precise, references to any idea concerning the transmission of images in Chinese sources are few. An early folktale concerns a princess of the Tang Dynasty named Li Wencheng, or Wencheng Gongzhu (文成公主). She was married off to the Tibetan king Songtsän Gampo. The story recounts how the princess’ father gave her a special mirror that would allow her to see Chang’an (modern Xi’an).

A late ninth-century Chinese collection of anecdotes entitled Duyang Zabian (杜陽雜編 Compilation of Miscellanea from Duyang) describes a special pillow(!) sent from a distant country.

The description of this zhong ming pillow suggest another fantastical viewing device. A literal translation of the name of the device is not particularly helpful. The Chinese characters are: 重明枕 (zhonɡ minɡ zhen); the first character (重 zhonɡ) means ‘serious’ or ‘to attach importance to’, the second character (明 ming) means ‘bright’ or ‘clear’, and the last character (枕 zhen) indeed means ‘pillow’. The translation of the term as a whole, then, would be ‘a pillow which values brightness’.

The idea of an entire scene that is rendered visible in a pillow is vaguely echoed in a mention — in a very different kind of work — concerning a moving image observable in a special mirror. The device is recounted in a text entitled De abditis rerum causis (On the Hidden Causes of Things) by the physician Jean Fernel (1497 - 1558). This work takes the form of a dialogue among three interlocutors, and examines philosophical questions — rather than physiology, which was the focus of Fernel’s other investigations. A passage in the text runs as follows:

“I have seen a person use the power of words to divert various phantoms into a mirror, images that promptly displayed there whatever he requested, either in writing or in genuine images, so lucidly that everything was being rapidly and readily recognized by those present”.

This passage appears in a longer discussion about what Fernel calls daemones (demons) — that is, spirits that affect human affairs. The language is obscure, and nothing in the rest of the text clarifies what Fernel is talking about here. Moreover, this seems to be part of the general tradition of catoptromancy, the use of mirrors in the context of the practice of magic. However, from Fernel’s description, the modern reader might imagine something like a computer screen responding to commands — “images that promptly displayed there whatever he requested, either in writing or in genuine images”. Certainly, a vivid technological imagination was at work here, even with the inclusion of “phantoms” in the description.

Technology in Different Contexts

The passages describing devices for viewing images certainly are not purely technical descriptions, but at the same time they cannot be read as pure fantasies, either. Indeed, the attempt to place the various texts that discuss such devices into contemporary categories of fiction, non-fiction, technological treatises, and so on, is anachronistic. These earlier writers viewed their sources and their ideas in a much more holistic manner, and thus the more rational parts of the texts — such as the mention of basic optical principles — are embedded in what a modern reader would consider more fanciful material.

This embedding was not done consciously — the texts, in short, are what they are. But looking at them collectively, some conclusions might be drawn: the most conservative conclusion might be that these writers were interested in the possibilities of technology. In the periods when these texts were written, there obviously was an intersection between craft, existing technological capabilities, and speculations about potential technological capabilities, along with beliefs in magic, animism, and so on. Moreover, in a later period when particular inventions for obtaining images from afar — such as telescopes — were a reality, the actual discovery of such devices at times seem to have been “backdated” and attributed to ancient sources.

Technological discussions — perhaps much more than today — were contextualized in all kinds of writing. In the case of these ‘mirrors’, and the less well-defined devices that supposedly allowed one to observe scenes at a distance, this was also the case. The practice of including these devices in a tale also seems to be very old; concerning tale type AT653A, where a special ‘telescope’ allows one to see what is happening far away, the scholar of folklore Steven Swann Jones notes: “What appears to be the most satisfactory answer to the origin of AT653A is the proposal that, as an essential narrative pattern, its history may extend back over three or four thousand years. In essence, this suggests that AT 653A is a prehistorical tale known both to Africans and Indo-Europeans that became a part of both their folkloristic heritages. This conclusion demonstrates the ultimate limitations of origins scholarship when trying to identify the authorship of possibly prehistory.”

This implies that even thousands of years ago, in a wide range of cultures, oral storytellers — and later, writers — pondered the possibilities of technological devices, even if the contexts seem peculiar to 21st-century readers.

Dr Benjamin B. Olshin is a former Professor of Philosophy, the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, and Design at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. His areas of expertise include sociology of science and technology, design, Eastern / Western philosophy, as well as cross-cultural management. His latest book is: Lost Knowledge: The Concept of Vanished Technologies and Other Human Histories.

Top Image: Mirror magic, fortune telling and fulfillment of desires. Fantasy with a mirror, dark room, magical power, night view. (MiaStendal /Adobe Stock)

References

Bacon, F. 1989. New Atlantis and The Great Instauration. Jerry Weinberger, ed. Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson.

Bacon, R. 1962. The Opus Majus of Roger Bacon, 2 vols. Robert Belle Burke, trans. New York: Russell & Russell.

Bartlett, R. 2008. The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

Bascom, W. R. 1975. African Dilemma Tales. The Hague: Mouton Publishers.

Brewer, K. 2015. Prester John: The Legend and its Sources. Farnham: Ashgate

Chen, F.L. 2007. Chinese Shadow Theatre: History, Popular Religion, and Women Warriors. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Cohen, A. M. 2006. Shakespeare and Technology: Dramatizing Early Modern Technological Revolutions. Palgrave Macmillan.

Coyle, J. K. 2009. Manichaeism and Its Legacy. Brill.

Ellis, R. P. 2015. Francis Bacon: The Double-Edged Life of the Philosopher and Statesman. McFarland & Company.

Gallaga, E. and Blainey, M.G. eds. 2016. Manufactured Light: Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm. Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Grabes, H. 2009. The Mutable Glass: Mirror-imagery in Titles and Texts of the Middle Ages and English Renaissance, Gordon Collier, trans. Cambridge University Press.

Gulácsi, Z. and BeDuhn, J. 2015. Picturing Mani’s Cosmology: An Analysis of Doctrinal Iconography on a Manichaean Hanging Scroll from 13th/14th-Century Southern China. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 25

Jones, S. S. 1976. The Rarest Thing in the World’: Indo-European or African? Research in African Literatures 7.2

Kósa, G. 2014. Translating the Eikōn. Some Considerations on the Relation of the Chinese Cosmology Painting to the Eikōn”, in Jens Peter Laut and Klaus Röhrborn, eds., Vom Aramäischen zum Alttürkischen. Fragen zur Übersetzung von manichäischen Texten. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter

Lockhart, J. 1993. We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press

Mack, R. L., ed. 1995. Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Mark A. and Fisher, J.H. eds. 2012.The Complete Poetry and Prose of Geoffrey Chaucer. Boston: Wadsworth.

Molland, A.G. 1974. Roger Bacon as Magician. Traditio 30

Price, B. ed. 2002. Francis Bacon's New Atlantis: New Interdisciplinary Essays. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Slessarev, V. 1959. Prester John: The Letter and the Legend. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Sterne, J. 2003. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham: Duke University Press.

Von Nettesheim, A. and Cornelius, H. 1993. Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Donald Tyson, ed. and James Freake, trans. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn

In so far as writing is concerned, any one can write anything, in any language, at any time, any where in the world (fiction). As to ascribing a meaning or an applied context to it, is, (as you're attempting to do) an entirely different matter. Perhaps the word mirror was wrongfully presumed (absent mindedly) to be a telescope (a wishful thinking, on somebody's part) by one writer of wayward fiction, in the past. In the world of fiction this idea spread like a wild fire. So what?

I fail to see the purpose or a meaning (other than mere amusement) of this long article, couched well, but to no meaningful account. It is certainly, not a literary piece or an object of art. Sorry!