The House of Uruk, Greatest of Sumerian Heroes

The greatest of all Sumerian heroes were said to have belonged to the first House of Uruk. For the Sumerians, this House of Uruk was not just another royal house, for them it was one of the greatest Sumerian dynasties ever to have ruled over Sumer, if not the greatest.

According to the Sumerian King List, the first House of Uruk, nowadays called the First Dynasty of Uruk, descended from the sun god, Utu. For the ancients, this superhuman descent was visible in the great and mighty deeds done by heroes, mighty men like Enmerkar, Lugalbanda, Dumuzi and Gilgamesh. Deeds reflected in the great monuments attributed to them, dated to the Uruk Period (c. 3800-2850 BC), to this very day confirming the fact that the House of Uruk yielded one of the most remarkable and outstanding epochs in ancient Mesopotamian history.

Meskiagkasher: Founder of the First House of Uruk

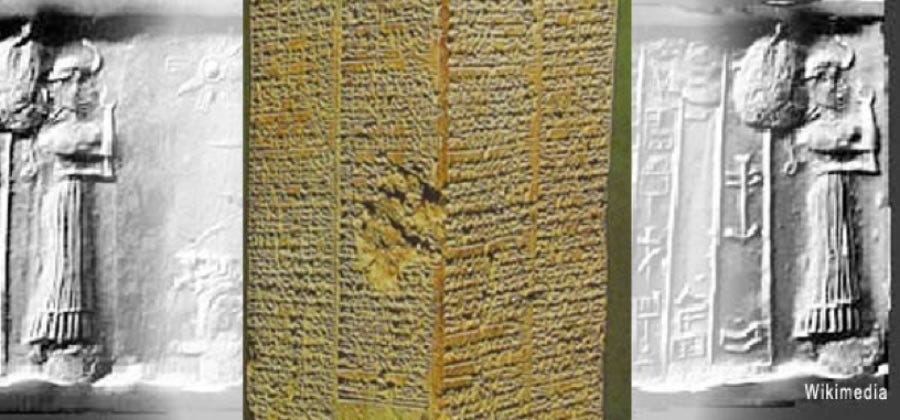

The names of the earliest Urukite rulers appear in the Sumerian King List. As most of the kings of this dynasty ruled before phonetic writing was discovered allowing for the documentation of royal reigns, there can be no doubt that the King List only comprises those kings remembered in the oral tradition.

According to the Sumerian King List, the king who founded this dynasty after the great deluge was Meskiagkasher. He was both high priest and king: “In E-anna(k) Mes-kiag-kasher, son of Utu, became high priest (“en”) and king (“lugal”) and reigned 324 years. Mes-kiag-kasher went into the sea and came out (from it) to the mountains.”

Although the first House of Uruk had a very special place in Sumerian history, as those belonging to an exceptionally great and heroic age, this dynasty does not appear at the top of the Sumerian King List but lower down. This, however, does not reveal much about the exact time they ruled over the land of Sumer since the King List was first compiled much later. The compiler of this list did not know how the reigns of the early dynasties were related to one another and merely wrote them down one beneath the other, leaving the wrong impression that Sumerian history happened in that order. He also accorded the great rulers reigns of hundreds of years, which is unfortunately difficult to interpret.

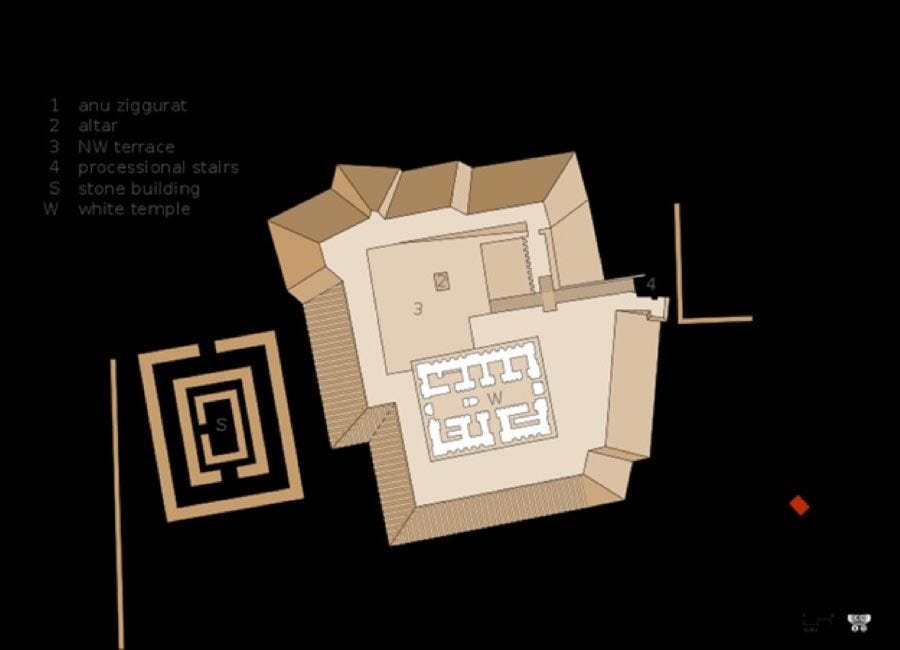

Fortunately, the mighty deeds attributed to the great legendary kings of the first House of Uruk can be used as a compass to find each one’s place in ancient Sumerian history. There is a remarkably consistent agreement between the literary traditions and the archaeological finds made in that ancient land. Thus one can figure out that this family came to Sumer right at the start of the so-called Uruk Period when the great city of Uruk was first built. This is in line with the textual tradition, according to which Meskiagkasher became king at E-anna, ‘house’ or temple of An, and his son, Enmerkar, built the city of Uruk on this site.

The Great City of Uruk Became Sumerian Powerhouse of Technology, Architecture and Culture

The White Temple and the Great Ziggurat in the Mesopotamian City of Uruk

The Ancient Epic of Gilgamesh and the Precession of the Equinox

The Uruk Period in Mesopotamia is separated from the older Ubaid Period by a clear change in material culture, a change in cultural remains found in the archaeological record, which coincides with the 2.7 to 3.7 meter (8.85 – 12.14 feet) flood layer discovered at the ancient city of Ur by the British archaeologist, Sir Leonard Woolley. Various scholars have argued this is where the great flood of Sumerian and ancient Middle Eastern tradition fits into their history, a deluge remembered as an extraordinary and very drastic event in Sumer’s past. Archaeologists also found evidence of this flood at places like Uruk, Eridu and elsewhere in the area.

Although breaks in settlement are often difficult to detect since successive layers of settlement cannot always be clearly distinguished from each other, one can observe a corresponding fall in population density throughout the region during this time. In the immediate period after the flood many people came as new settlers to the vicinity of the An temple. This agrees with the stories about Meskiagkasher, founder of the first House of Uruk, who is said to have come to that area in the time before the city of Uruk was built there. According to the stories told about this family, they came to Sumer from the mountainous land of Aratta in the north.

Enmerkar: The Great Builder King

Meskiagkasher’s descendants, were remembered as great rulers, some of whom as the greatest rulers the land of Sumer had ever seen. Their stories were told and retold by bards throughout Sumerian history until they were eventually written down in the Ur III period at the end of the third millennium BC. A.R. George writes: “The early rulers of Uruk had a great impact on poets of the third millennium [BC], much as the Trojan War and its aftermath had on Homer. The reigns of Enmerkar, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh entered legend as the heroic age of Sumer. One can imagine that court minstrels and storytellers began to compose oral ‘lays of ancient Uruk’ soon after the lifetimes of these heroes.”

Four Sumerian poems telling about the exploits of the heroes Enmerkar and Lugalbanda exist. They focus on the conflict between Sumer and Aratta and are called the Matter of Aratta. Together with the stories about Gilgamesh they form the Gesta Urukaeorum, the legends of the kings of Uruk. These legends provide the basic literary corpus about the lives of those legendary kings.

The Sumerian King List lists Enmerkar as the son of Meskiagkasher and according to literary tradition, he was born and raised in the land of Aratta. Some markers for the location of this land do fortunately exist. In one of the stories about Enmerkar, Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, the land of Aratta was reached through seven mountain passes from Sumer in the south: “Five, six, seven mountain ranges he [Enmerkar’s messenger] crossed. And when he lifted his eyes, he had arrived in Aratta.” These seven mountain passes were well known in ancient times and many years later the Assyrian king, Sargon II, also travelled through them to battle against Urartu, seemingly the later form of the name Aratta. When he arrived at his destination just south of Lake Urmia in the far northwestern parts of present-day Iran, he crossed the Aratta River. This is the only geographical landmark in later literature pertaining to this land.

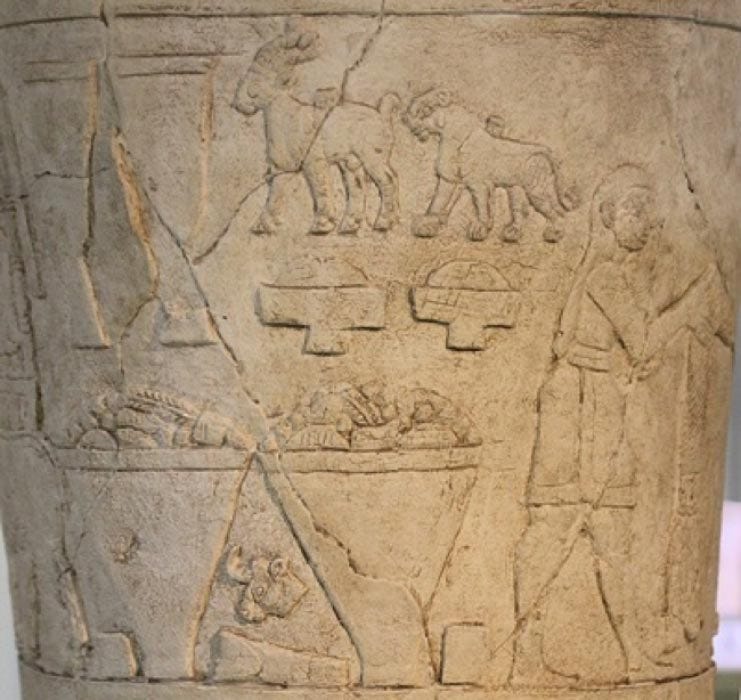

Enmerkar is primarily remembered as the one who built the city of Uruk. To accomplish this task, he asked the ruler of Aratta to send him builders and metalworkers to help not only to build this city but also to rebuild Eridu’s temple. In this early period, Sumer did not have these skills and all the metals, precious stones and building materials, such as limestone and wood, had to be imported from the north. This request is described at length in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. At that time, a large part of the land comprised marches that had to be drained for the land to be reclaimed. In time, Uruk became a mighty city, the only such city in Sumer during the Uruk Period, stretching over 250 hectares with about 10- to 50 000 inhabitants. Great buildings and temples adorned the city.

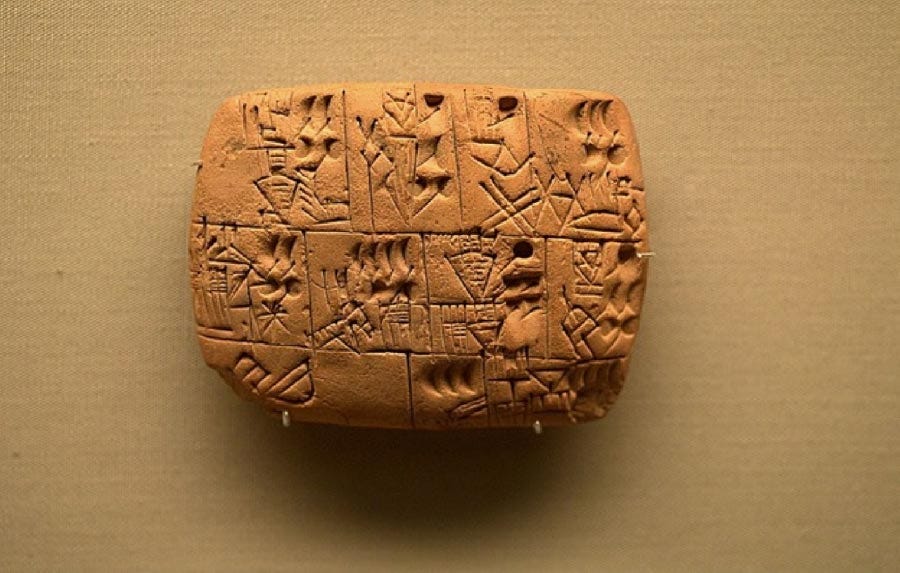

Enmerkar is also remembered for other inventions. According to Sumerian tradition, he was the first to have: “smoothed clay with the hand and set down words on it in the manner of a tablet. Right up to then there had been no one setting down words on clay.”

Although the author, who wrote this down long after these events took place, says the words looked like ‘nails’, in keeping with the cuneiform tradition, this merely reflects his idea that writing has always looked like this. The earliest writing from the Uruk Period was, in fact, not done with a stylus as in later times but with a pointed instrument, making pictographic symbols not looking as formal as in later times. At first, they merely used these for accounting purposes and only towards the end of the Uruk Period were these symbols read phonetically for the very first time.

Another of Enmerkar’s feats was that he produced surplus grain to be traded. He also brought the worship of the goddess Inanna from Aratta to the temple of An, where Uruk was later built.

Lugalbanda: Warrior-King of Uruk

According to the Sumerian King List, the next king of Uruk was Lugalbanda. The name Lugalbanda means ‘little king’. Lugalbanda’s story is told in two parts, namely Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave and Lugalbanda and the Thunderbird. The first part tells how King Enmerkar devised a campaign against the land of Aratta in the north. He called the people up to arms and placed them under the command of eight warrior-leaders, namely Lugalbanda together with seven other young men.

In the second part of the story, Lugalbanda found himself in the Thunderbird or Anzu’s nest, which is already in the first part of the story said to have been high up in the god Enki’s ‘eagle’ tree. According to this story, this experience led to him being reckoned as part of the Anzu-bird’s family. According to tradition, Lugalbanda played an important role in establishing the Anzu as a cult symbol in ancient Sumer. The first depictions of this lion-headed eagle, do, in fact, date back to the Uruk Period.

The portrayal of Lugalbanda as a conquering warrior-king indicates professional armies came into existence in Sumer during this time. This is confirmed by history. For the first time during the last phase of the Uruk Period, one finds fortified structures on the plains as well as the highlands from where garrisons could control large areas, and one also finds depictions of war in art as well as deposits of weapons were found in Uruk and surrounding areas.

Towards the end of the Uruk Period, the Sumerian influence became widespread all across Mesopotamia. Uruk enclaves were established up along the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, all the way to the Taurus mountains in the northwest and the Zagros mountains in the northeast.

Dumuzi A Tragic Figure

After Lugalbanda, according to the King List, came Dumuzi. There are, however, no great epics telling the story of this king and he was remembered more in cultic tradition. He was a tragic figure who died as a young man during the ‘festival of young men’ (war), more specifically, during a rebellion when the cities surrounding Uruk apparently rose up against its rule over them. Evidence indicates this happened at the end of the Uruk Period, or the Uruk IV Period. Depictions on seals and other items show prisoners with their hands fastened behind their backs, being pushed by guards to the ground with spears and clubs.

Dumuzi’s cult became especially widespread and popular among farming communities, where his death was closely related to the harvest, when grain and dates were cut and harvested. With Dumuzi’s death, the rule of the first Dynasty of Uruk came to an end. Now, another city rose to prominence, namely Kish, where Enmebarragesi became king. He is the very first Sumerian ruler whose inscriptions were found, done in a very early style of writing, using straight lines instead of the typical nail type cuneiform that came into use later.

Gilgamesh: Builder of Uruk’s Great Walls

There was, however, another scion of the first House of Uruk, who would eventually reclaim the throne of Uruk. This is the well-known Gilgamesh. For some reason – possibly related to the events surrounding Dumuzi’s death – he took shelter at the court of Enmebarragesi’s son Akka. One reads in Gilgamesh and Akka that Akka appointed Gilgamesh as governor of Uruk. The young men of the city, however, incited Gilgamesh to lead an uprising against the yoke of Kish. During the ensuing battle with Akka, Gilgamesh came out victorious and subsequently became the king of Uruk.

As ruler of Uruk, Gilgamesh was especially remembered as the one who built the great walls of the city. These are beautifully described in The Gilgamesh Epic. The foundations of the wall were made from burnt brick whereas the walls themselves were constructed from plano-convex bricks. The walls were seven meters high (23 feet) and nine kilometers (5.6 miles) long and incorporated high towers and strong gates. In keeping with tradition, it dates back to the time directly after the final phase of the Uruk Period (Uruk IV), from the Jemdet Nasr Period.

First Dynasty of Uruk in Summary

The first Dynasty of Uruk was remembered as the greatest heroic epoch of the Sumerian people. Rulers from this dynasty such as Enmerkar, Lugalbanda, Dumuzi and Gilgamesh were awarded a unique place in Sumerian history – they were remembered as unmatched heroes from an age which had no equal in later history.

According to Sumerian tradition, Meskiagkasher was the founder of the first House of Uruk. His migration to the An temple area before the city of Uruk was built there is in line with archaeological evidence about such a settlement at the start of the Uruk Period. Enmerkar built the city of Uruk and invented writing, both which happened during the Middle Uruk Period. Lugalbanda, the warrior-king of Uruk, fits in nicely with the period of the Uruk-expansion, when the Sumerians built fortified structures on the plains and in the highlands, when their influence spread into the Taurus and Zagros mountain regions. The tradition of him introducing the Anzu-cult finds confirmation in the first depictions of this lion-headed eagle during the Uruk Period.

The last ruler of this dynasty, Dumuzi, was a tragic figure and evidence points towards political instability. After him came Gilgamesh, to whom the building of the great walls of Uruk is attributed, walls which date from the Jemdet Nasr Period. One can surmise that the stories of these great heroes might have been based on those of true historical persons who ruled during that time – persons of whom one has no physical evidence that they lived except the great epic tradition their poets left as their legacy.

Dr Willem McLoud is an independent South African scholar whose main interests are ancient Middle Eastern studies, Kantian philosophy and philosophy of science. Willem’s main areas of study regarding the ancient Middle East are the Sumerian, Akkadian and early Egyptian civilizations, with special focus on the Uruk and Akkadian Periods in Mesopotamian history as well as the Old Kingdom Period in Egyptian history.

Top Image: Mesopotamian king as Master of Animals on the Gebel el-Arak Knife, dated circa 3300-3200 BC, Abydos, Egypt. (CC BY-SA 2.0)