The Hidden Blueprint in Rosslyn Chapel’s Window of Wonder

Located on a picturesque hilltop six miles south of Scotland’s capital city of Edinburgh, is one of the world’s most mysterious and misunderstood buildings - Rosslyn Chapel. This tiny Scottish church came under the world’s spotlight after Dan Brown’s 2003 thriller The Da Vinci Code connected it with the mystery of the Holy Grail. If the word ‘Grail’ means much more than a chalice that allegedly captured the blood of Christ, or a holy blood lineage, and refers more to ‘lost ancient knowledge’, then it is indeed hidden within the walls of Rosslyn Chapel.

Medieval Church Architecture

Founded in September 1446 AD by Sir William St Clair, Third Earl of Orkney, construction at Rosslyn ceased upon the death of its founder in 1484 and it was never completed. The building seen today is the choir of what was intended to be a much larger collegiate church designed to be cruciform in shape. The east gable wall features the largest arched window within the building and its highly detailed stone tracery and stained-glass inlays are Victorian additions.

Medieval Christian buildings were regarded as vessels for the transmission of Biblical information and designers embedded religious concepts by symbolically grouping architectural features such as windows and doors, fonts, altars, pillars and even roof pinnacles. Rosslyn Chapel’s Victorian east window is highly symbolic and a wonderful example of medieval church designers expressing fundamental Christian principles using geometry and stonemasonry as media.

Firstly, the east window design is composed with five primary symbolic features: a circle, a square and a cross situated above two arches. In the mid-15th century, many ecclesiastics and occultists in Europe played with alchemical concepts entangling the circle, square and triangle with ancient Greek cosmology. For example, the Bible makes reference to earth having ‘four corners’, thus, many Christian designers used square and double squares to represent ‘earthly’ concepts. Richard Taylor’s informative book How to Read a Church: A Guide to Symbols and Images in Churches and Cathedrals, informs that: “circles, perceived as perfect, endless and infinite were used to represent divine and heavenly concepts. Triangles expressed the perceived threefold nature of deity and therefore in Christian buildings triangular symbols and features most often represent the holy trinity Father, Son and Holy Spirit.”

The upper part of Rosslyn’s east window is composed of a circle, a square and a cross; and the designer’s message is hidden not only in these shapes, but in how these three elements interact with one another.

Attempting to interpret the window design: the cross is placed ‘within’ the circle and ‘over’ the square. Accepting the square represents earth and the cross represents man, surrounded by and connected to the divine (circle), Rosslyn’s east window in its entirety, urges viewers to consider the oneness of man, heaven and earth.

Geometry, Numerology and Sacred Architecture

By the 10th century, Islamic geometers had figured out how to erect pointed arches with geometric applications of the circle, square and triangle, knowledge which might have come from a deep understanding (and later worship) of the cube and its properties. The cube was regarded as a representation of God in Islam, Judaism and Christianity and it was used in the building plans of the Biblical Holy of Holies in Solomon’s Temple and at the Kaaba, the holy black stone in the center of the Grand Mosque in Mecca.

Interpreted spiritually, the cube’s 1:1:1 ratio defined both the oneness and the three-fold aspects of deity. But in the practical world, with cubes, designers could establish a series of interlocking squares and triangles and it was this deeply esoteric property that gave rise to the two fundamental building methods; ad quadratum - building to the square, and ad triangulum - building to the triangle, upon which all medieval temples, churches, chapels and cathedrals were raised.

Double square designs were of great significance to ancient architects because the inherent 2:1 ratio was related to music through the octave, and this format came to dominate the designs of most European gothic cathedrals and churches. On a practical level, double square foundational plans were simple to work with and the resultant buildings were stronger than other formats; therefor they supported vaulted roofs better than other designs.

As well as using geometry to express religious concepts, numbers associated to characters and events in the Bible were often used as measuring units and building modules, in religious buildings. A good example of this is seen at Rosslyn Chapel which is dedicated to St Matthew, and the numbers which reoccur most often in the Book of Matthew can be observed within the building’s foundational measurements and architectural features.

Respected Scottish historian Robert Brydon FSA Scot wrote in Rosslyn and the Western Mystery (1996): “the numbers seven and 14 reoccur in the Book of Matthew” and that these numbers feature repeatedly within Rosslyn’s architecture, for example; the central arrangement of Rosslyn’s pillars totals seven arches with 14 columns. A second number system exists in Rosslyn Chapel’s architecture which can be related to the Book of John: 12, 24, 36, 72, 144….

This number system was very popular with medieval Christian designers and was used in the foundational measurements of York Minster cathedral, which is built upon a double square plan measuring 144 feet (43.89 meters) wide. Durham Cathedral is also founded on a double square measuring 72 feet (21.94 meters), half of 144 feet and in France, both Amiens and Chartres Cathedrals are 144 units high. At Rosslyn Chapel, measuring from window to window the length of the building is 72 feet (21.94 meters) and the width is half the length at 36 feet (10.97 meters). Thus, Rosslyn Chapel forms a double square of 72 x 36 feet (21.94 x 10.97 meters), conforming perfectly with the number system derived in the Books of Matthew and John.

Having discovered the fundamental measurements of Rosslyn Chapel reflected numbers in the Books of Matthew and John, the 36, 72 and 144 numbers can also be measured elsewhere within the building. Returning to the Victorian east window, the circle is decorated with 48 points, the cross has a further 56 and the two lower arches are embellished with 20. Therefore, the total number of geometric points within the east window is, beautifully, 144.

Applying the Secret Window Code

The point within a circle (circumpunct) was the primary step in all ancient design procedures and became a universal glyph for light, the point representing the sun’s first creation. Greek mathematical philosophers regarded the circumpunct symbol as ‘monad’, a word derived from monas, meaning unit, single or oneness, the womb from which all preceding geometric forms were born.

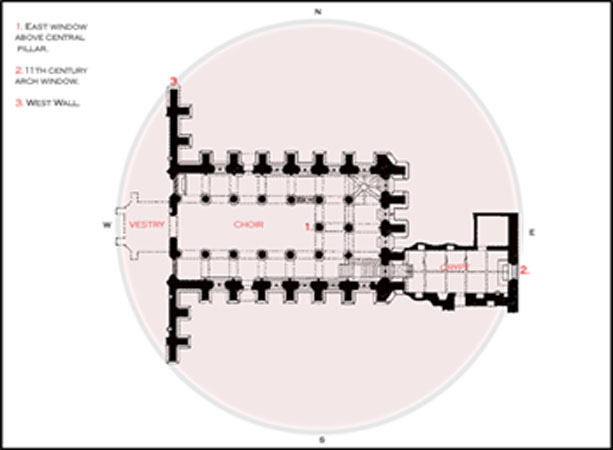

Rosslyn’s roof forms a peak above the east gable window at the highest point of the building, directly above the inner central pillar. Extending a radial measure from this center point to the furthest extremes of the architecture; the northern and southern extremes of the west wall are located exactly 68 feet (20.72 meters) away. This wall was originally intended to be the east wall of the transept in the cruciform building and the circumference of this governing circle also locates the west face of the vestry at the western extreme of the chapel.

The circumference of this governing circle also locates a 12th-century arched window in the lower Sacristy, to the east. This older building was existent some 400 years before Rosslyn Chapel was built, but it was included as a functional part of the 15th-century church. Finding this 12th-century window located directly upon the circumference of the 15th-century geometers’ circle, reveals the 15th-century designers as having measured from this arched east window (2) to establish a location for their new building’s center pillar (1).

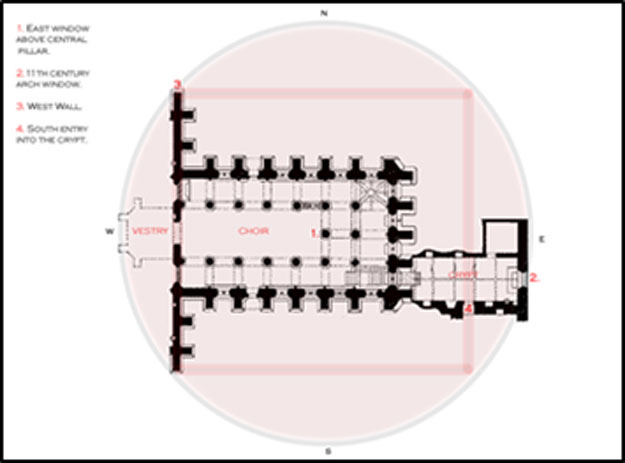

Reading the message of the east window; it displays a square inside a circle and architects knows this as ‘circling the square’. When this primary geometrical concept is applied to Rosslyn’s ground plan (below), the west wall (3) has evidently been located upon the west face of the square and the southern doorway into the sacristy is situated perfectly on the eastern face of the square.

Having overlaid the circle and square onto Rosslyn’s ground plan, when the cross shape is applied, it becomes clear that Rosslyn’s interior pillars were spaced with the same proportions and ratios seen in the east window cross design.

Once the governing dimensions for a building had been determined, to establish accurate locations for alters and fonts so that they related geometrically to the scheme of the greater building in ratio and proportion, designers progressively reduced the governing circles and squares. Applying this technique to Rosslyn’s ground plan, the designers’ method of locating the chapel’s main components - doors, windows, pillars and pinnacles - are all precisely located upon the circumference of circles, on the sides of squares and at the intersections of both, as seen (below).

When this circling and squaring action is repeated five times, the central arrangement of eight pillars is squared, framing the center pillar as the point from which all other parts are related through proportion, ratio and geometry. It can be concluded that the Victorian east window in Rosslyn Chapel is a ‘blueprint for the chapel’ hidden in plain sight. While millions of Grail hungry tourists have trotted through Rosslyn Chapel seeking signs pointing to the resting place of the Holy Grail, few have sat still for long enough gazing at the mandala that is the east window, in which the knowledge of the ancients has been embedded.

Ashley Cowie is a Scottish historian, author and documentary filmmaker presenting original perspectives on historical problems, in accessible and exciting ways. His books, articles and television shows explore lost cultures and kingdoms, ancient crafts and artifacts, symbols and architecture, myths and legends telling thought-provoking stories which together offer insights into our shared social history. www.ashleycowie.com.

Top Image: Rosslyn Chapel (CC0)

By Ashley Cowie

Brown, D. 2003. The Da Vinci Code, Double Day Publishing.

Brydon, R. 1996. Rosslyn and the Western Mystery. Available at: https://www.rosslynchapel.com/shop/rosslyn-and-the-western-mystery-tradition/

Hillenbrand, R. 1999. Islamic Art and Architecture. Thames & Hudson World of Art series; London.

Taylor, R. 2005. How to Read a Church: A Guide to Symbols and Images in Churches and Cathedrals. Hidden Spring.

"By the 10th century, Islamic geometers had figured out how to .... ". I'm curious, how do we know it wasn't known prior to the 10th century? 99.9% +/- of all ancient structures that might have had this knowledge incorporated into them, have long since been leveled. I assume the 10th century conclusion is an assumption.

Rosslyn’s east window isn’t just a work of art, it’s a coded manuscript in stone, echoing sacred geometry and ancient wisdom across centuries