The Divine Guardians & When East Meets West in Japan's Sacred Spaces

The Unlikely Sentinels of Sensō-ji

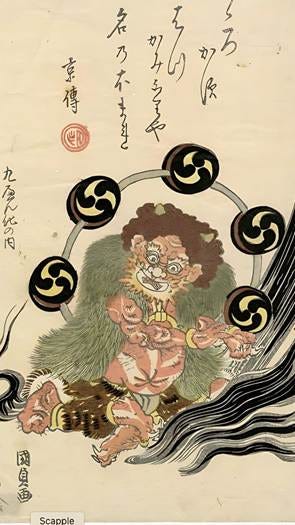

At the main gateway to Sensō-ji, Tokyo's oldest Buddhist temple, two unlikely guardians stand watch. Both are fearsome, with the kind of fiery hair often used in manga and anime, alongside bulging, angry eyes. One, Raijin, holds a hammer and is surrounded by taiko drums. The other, Fūjin, bears a snake-like bag across his shoulders. Together, they tell a story of extraordinary parallels and connections stretching across centuries and many thousands of miles, giving life to the cosmos out of which so much Japanese art and culture was born.

The reason that Raijin and Fūjin make for unlikely guardians at Sensō-ji is that they are Shintō deities, not Buddhist ones. In fact, they are two of the very oldest deities in the entire Japanese pantheon. The origins of that pantheon lie in two creator deities: a god called Izanagi and his sister Izanami. Their story is ultimately a tragic one.

The Creation Myth: Love, Loss, and Divine Tragedy

Together, Izanagi and Izanami created the world as we know it. Izanagi dipped a spear into the ocean, and a droplet that fell when he withdrew it became the first island. Later, they were married, at first producing a shadowy and unwanted 'leech child' named Hiruko (who was cast adrift in a reed-boat) but later enjoying famous success: the first of the Japanese islands were born from their union.

Then tragedy struck. Izanami died while giving birth to the fire god. Bereft, Izanagi embarked on a journey into the underworld – known as Yomi – to reclaim her. The parallels with the story of Orpheus and Eurydice in Greek mythology are really striking here. Both men lose their wives and both travel to the underworld to get them back. When he arrives in Hades, Orpheus is told that Eurydice will be restored to him – on one condition: he must not look back at her until they emerge into the sunlight. Izanagi, too, was told in the underworld that he must not look at Izanami in her deathly state.

Both men are given the same warning. Both make the same mistake.

Love and longing force Orpheus to look back, to make sure that Eurydice is following along behind him. She is immediately pulled back into the underworld, never to re-emerge. Izanagi is fired by curiosity. What does Izanami look like, after death? He steals a glance – and sees her body decayed, crawling with maggots. Shocked, he flees the underworld without her. Izanami is outraged and sends the 'hags of Yomi' chasing after him. Izanagi just about makes it out of the underworld alive, rolling a large boulder across the entrance before Izanami's vengeance can reach him.

As far as we know, these stories of love, loss and doomed attempts at restoration emerged independently of one another in Europe and Japan: a universal response, it seems, to the tragedy and finality of death. But the story of Izanami doesn't end there. From her decaying body were born all sorts of terrible deities – including Fūjin, the god of wind, and Raijin, the god of thunder. Born in Yomi, they somehow escaped into the world above, to become two of the best-known members of the Japanese pantheon.

The Sun Goddess and Divine Hierarchy

At the apex of that pantheon stands the sun goddess Amaterasu: a daughter of Izanagi and ruler of the heavenly plain. Like Apollo in the Greek tradition, she represents illumination, order and civilization. And like Demeter, goddess of grain and fertility in Greece, when she withdraws from the world it can mean disaster. On one occasion, Amaterasu withdraws into a cave and the world is cast into darkness – just as Demeter withdraws from the world in grief after the abduction of her daughter Persephone, causing crops to fail and raising the spectre of famine for ordinary mortals.

Amaterasu became important in Japan from around the 500s CE, when she was adopted as the titular deity and divine ancestor of the Yamato clan, then at the beginning of their rise to become what we now know as the imperial family. Around the same time, Buddhist texts and images began to make their way into Japan from Korea and China. This raised a question: how were Buddhist deities likely to get on with the native gods of what came to be called Shintō (literally 'the way of the gods')?

The Art of Religious Syncretism

Some worried that it must certainly mean war. When a disastrous epidemic struck Japan, a Buddhist statue was duly thrown into a canal – a way of showing the Shintō gods that their message had been heard, loud and clear.

But in time, Buddhism managed to gain a foothold in Japan, contributing to a hugely important feature of Japanese culture: syncretism. In a dangerous, unpredictable and largely unknowable world, surely it made sense to have all the friends you could get? Alongside this ran a deep and abiding awareness amongst Buddhist monks and nuns that they must always demonstrate their usefulness to the Japanese state and to its imperial family. Ways were therefore found of mixing Shintō with Mahayana Buddhist pantheons, inspired by similar efforts in China to blend Buddhist with Daoist and local folk deities.

In architectural terms, this meant Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples often being constructed on the same site. In conceptual and artistic terms, it meant connecting a particular Buddhist deity with a particular Shintō deity, by claiming that they were aspects or emanations of the same god. One of the most important pairings, on and off down the centuries, was Amaterasu with the bodhisattva Kannon: two female deities who represent different aspects of light and goodness.

Another was Daikokuten: a Buddhist deity ultimately derived from Hinduism's Shiva, who morphed in Japan into a figure associated with prosperity and good fortune and who became associated with a Shintō deity called Ōkuninushi. He is now one of the most recognisable figures in Japanese religious culture: cheerful and rotund, with accentuated earlobes – representing wisdom and good fortune. He is to be found often holding a mallet and sitting on rice bales.

Cross-Cultural Artistic Influences & The Silk Road Connection

Alongside this process of mixing and mingling ran artistic influences travelling the silk roads. The origins of Japan's wind god, Fūjin, are most likely indigenous: a response to the awesome power of the elements. But what is striking about that statue guarding the entrance to Sensō-ji temple in Tokyo is the bag across his shoulders. It contains wind, or winds, emphasising Fūjin's power. And it may have origins thousands of miles to the west, in the billowing cloak of Boreas, Greek god of the cold north wind. This imagery appears to have evolved as it travelled east in Greco-Buddhist art, becoming a wind-bag by the time it reached East Asia.

These parallels and transformations – gods crossing cultures, myths re-emerging in distant lands, images shifting as they travelled the silk roads – show us how much broader and stranger the history of religion and mythology is than any one tradition alone.

A Short History of Japan by Dr Christopher Harding is available in September.

Coming Up: A Deep Dive Into Divine Syncretism

The visual evidence of these cultural exchanges stands before us today in the guardian sculptures at Sensō-ji and countless other temples across Japan. The fierce expressions of Raijin, captured in both ancient woodblock prints and temple sculptures, tell a story that reaches back to the underworld of Yomi and forward to the cosmopolitan religious landscape of medieval Japan. Fūjin's wind bag, whether rendered in traditional art or carved in stone, carries with it the whispers of Greek winds that travelled the Silk Road.

In the upcoming podcast interview, we'll explore some of these themes in more depth. How did Gandhāran art carry Greek ideas into Buddhist temples? How were Shintō and Buddhist deities paired in Japan, in surprising and sometimes uneasy ways? And how did that cosy relationship finally fall apart in the modern era? Join us as we unravel the complex web of cultural exchange that gave birth to some of Japan's most enduring religious imagery and explore why these ancient guardians still watch over Tokyo's sacred spaces today.

Stay tuned for our conversation that will take you from the mythic underworld of Yomi to the bustling streets of modern Tokyo, revealing how ancient gods continue to shape contemporary Japanese culture.

Top image: Raijin drawing. 'Party in the Sky', by Utagawa Kunisada (1860). Source: Ukiyo-e.org.

By Dr Chris Harding

Dr Chris Harding is a senior lecturer in Asian History at the University of Edinburgh. He writes on wide range of topics, including history, politics, religion and pop culture, for publications including BBC History magazine, The Guardian, The Telegraph, UnHerd and The New York Times.

His new book, A Short History of Japan is available in September.

His substack newsletter, History with Chris Harding, is free to read and subscribe (link).

His Instagram account, History with Chris Harding.

Wonderful piece! Can't wait for the podcast.

Thanks for writing! Visited Edinburgh this spring w my family, and we were mesmerized!