The Coming of the Thunder People: Denisovan Hybrids, Shamanism and the American Genesis

In 2010 the existence of a previously unknown archaic human population was revealed following the DNA sequencing of a finger bone over 41,000 years old. It was discovered in 2008 in the Denisova Cave, a Stone Age site located in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. Three molars, two of enormous size, were also retrieved. They too belong to this same group of archaic humans, who are today known as the Denisovans.

Although to date these remain the only confirmed fossils relating to this extinct population, the sequencing of the Denisovan genome by the Department of Human Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, determined that many modern-day human populations carry Denisovan ancestry. Most of these populations are located in central, southern and eastern Asia. Others are found among the indigenous peoples of Papua New Guinea, Australia and the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific.

What about the Americas? Did the Denisovans’ impact on the continent prior to the submergence of the Beringia land-bridge around 8500 BC, which for tens of thousands of years had provided safe passage between the Russian Far East and Alaska?

Denisovan DNA

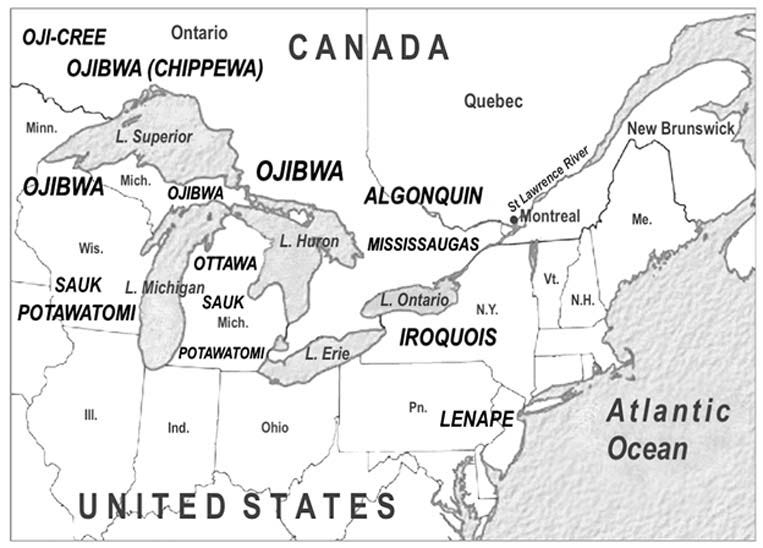

Various First Peoples in both North and South America possess significant levels of Denisovan DNA. This includes the Ojibwa, one of the largest tribes in North America. Their territories extend from Ontario in Canada down through the Great Lakes region into Minnesota and Wisconsin. Originally, their homeland was far to the east in the St Lawrence River basin (current Quebec). The Cree (or Oji-Cree) also possess Denisovan DNA, although not quite to the same level as the Ojibwa. Their ancestral home was immediately to the north and west of the Ojibwa in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the Northwest Territories.

The Anishinaabeg

Both the Ojibwa and Cree form part of what is known as the Algonquian language-speaking group, named after the Algonquin or Algonkin tribe. This collective of First Nations refer to themselves as the Anishinaabe (plural Anishinaabeg), meaning, ‘original people’ with a shared language known as Anishinaabemowin. Those belonging to this interlinked network of tribes, located in the northern and north-eastern parts of the North American continent, include the Potawatomi, Mississaugas, Cree, Chippewa, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and the Algonquin. Despite the ethnic and cultural unity of the Anishinaabeg, it is only the Ojibwa and Cree that possess significant levels of Denisovan ancestry (other tribes that do have it include the eastern Algonquin, whose surviving territories are beyond the north-eastern limits of the Great Lakes region, as well as the Tlingit of the Pacific Northwest).

Asian Origins

The ancestors of the Algonquian-speaking peoples are thought to have entered North America from East Asia. A study of First American DNA, based on the genome sequencing, suggests that the earliest peoples to arrive in North America came from East Asia around 23,000 years ago. By 12,500 years ago the population had split into two distinct branches. One moved southward contributing to the emergence of the first indigenous populations to occupy southern North America, Central America, and South America. The other branch headed eastward, forming the ancestors of various First Peoples including the Algonquin, Chippewa, Ojibwa and Cree. How exactly did the Ojibwa and Cree then come to possess so much Denisovan DNA? One major clue comes from a most unlikely belief found among the various Anishinaabeg tribes. It relates to legends concerning the prior existence on the continent of a mythical population known as the Thunder People.

Rise of the Animiki

In Ojibwa lore one of the most important groups of manitous (spirits) were the so-called Animiki´ (a-ni´-mi-ki), a name usually translated as ‘thunderbird(s), thunderer[s] thunder god[s]’, and, most enigmatic of all, the ‘thunder people’.

The thunderbird was considered a mythical bird, similar to an eagle or falcon. It controlled elemental forces such as thunder, lightning, storms, and rain. It was looked upon also as the divine source of the magic worked by the Ojibwa’s caste of wild shamans known as the Jes´sakkīd. They were seen by early settlers as jugglers, conjurers, or tricksters. Yet to the Ojibwa the Jes´sakkīd´ were healers, prophets, seers, as well as the ‘revealers of hidden truths’.

In addition to this the Ojibwa recognized the Milky Way as the ‘Thunderbird’s Path’, while the thunderbird itself was identified with the constellation of Cygnus. More commonly known as the Northern Cross, it is located where the Milky Way forks into two separate streams. For many First Peoples this celestial location was seen as the entrance to the land of the dead.

Even though thunderbirds existed as important spirit manitous, Ojibwa myths and legends speak of the Animiki´, or Thunder People, as ‘giant birds’ with clear anthropomorphic features. They lived in remote mountainous areas and were supposedly encountered by the first Anishinaabeg. According to American ethnologist Alanson Skinner (1923) the Algonquian-speaking Sauk of Wisconsin considered thunderbirds, the so-called ‘Feathered Ones’, as:

“giant eagles inhabiting the western Empyrean, but some maintain that they resemble human beings or, at least, are anthropomorphic at times. They dress like men and wear especially elegant fringed leather leggings.”

Earthly Animiki´ had the power to conjure thunder and lightning, the latter emitted from their eyes. For this reason, they were greatly feared, explaining perhaps the sheer potency of their memory among the Algonquian-speaking peoples. Is it possible that stories of the Thunder People preserve the memory of the former presence in the Great Lakes-St Lawrence River region of pronounced Denisovan hybrids? Was it from them that the Ojibwa and Cree gained at least some of their Denisovan ancestry?

The Thunder People and Mountainous Terrain

Tibetan and Sherpa populations of the Tibetan plateau possess a special gene, known as EPAS1, which allows them to live at extremely high altitudes. This gene, is now known to have been gained from interbreeding with Denisovans. Elevated, mountainous plateaus were thus the favored terrains of at least some Denisovan groups. Since the Thunder People were also thought to have inhabited mountainous regions, it increases the likelihood that stories surrounding them preserve the memory of surviving pockets of Denisovan hybrid descendants. They most likely reached North America from the Russian Far East, at a very early date, arguably even before 23000 BC, when the ancestors of the Algonquian-speaking peoples are thought to have entered the continent.

The Inuit of the Arctic region also possess two special genes that enable them to live in extremely cold conditions. These genes (TBX15 & WARS2) are now thought to have been inherited from the Denisovans. So, in addition to existing at very high altitudes, the Denisovans must also have lived in extremely cold environments for much of the time. This strengthens the argument that the Thunder People were perhaps hybrid descendants of the Asian Denisovans.

Thunderbird Shamans

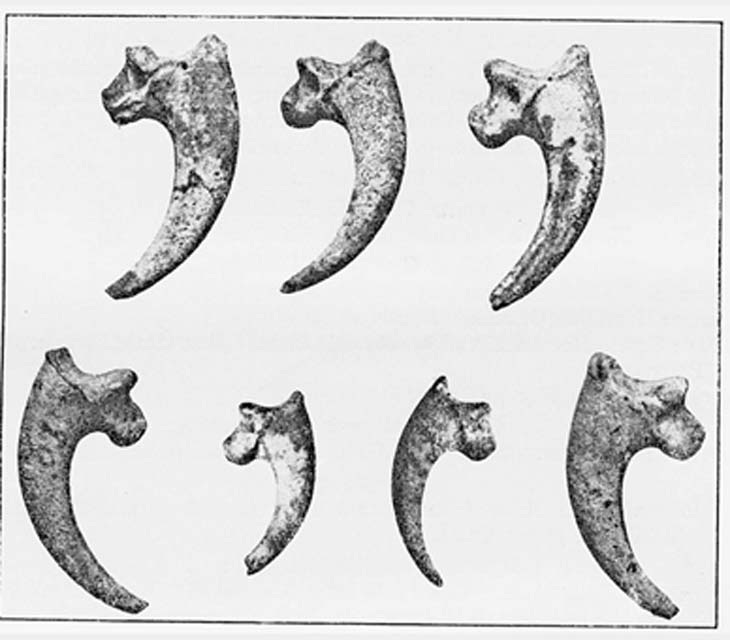

Legends regarding the earthly Animiki´ most likely relate to the existence of flesh and blood beings, who were considered to possess extraordinary powers, including the ability to control thunder and lightning, and bring forth storms and rain. Their identification with the mythical thunderbird indicates that they might well have worn coats of feathers belonging to the eagle, the principle animistic form of this mythical creature, and even those of corvids such as the raven. In Europe Neanderthals used dark feathers of raptors, vultures and corvids to create garments of dark feathers. They also wore necklaces of eagle talons, along with those of other large birds. Such distinctive forms of dress or decoration are unlikely to have been for aesthetic purposes alone. More likely they had a symbolic function, hinting at the existence of early forms of shamanism not only among Neanderthals, but also among the Thunder People of the American continent. Animism is used to create a link between the world of the living and perceived invisible realms, usually only experienced during dreams or altered states of consciousness. Shamanic rites involve assuming the spirit of a particular animal or bird to make the transition from this world to the realm of the spirit.

During shamanic experiences of this kind, spirit forms would be encountered. These might have included ancestral spirits, along with the denizens of both the Beneath World and the Upper World, a sky realm accessed via the Milky Way. On both the Eurasian and American continents the Milky Way was seen as a path or river along which the souls of the deceased, along with those of the shaman, were able to reach the sky world, often in the form of a bird. Paraphernalia a shaman might use for such practices included the wing bones and feathers of birds to achieve astral flight, skulls to link with the spirit or eyesight of the chosen animal or bird, and talons or claws to psychically attack potential enemies.

Autistic Gene

To achieve a link with their chosen animal or bird a shaman utilizes a natural empathy with the creature in question, something familiar to individuals associated with the autistic spectrum. Autism itself has long been linked with the roots of shamanism. A new study proposes that autistic genes generated by modern humans in harsh Ice Age conditions provided them with the mindset to leap ahead in everything from greater image retention abilities, to higher aptitudes in identifying and analyzing patterns of geography and movement.

Medical researcher, Barry Wright and archaeologist Penny Spikins, of the University of York, found such autistic talents enabled early modern humans to develop more efficient hunting tool kits, recall in absolute detail thousands of square miles of hunting terrain, and remember and analyze complex patterns of animal behavior.

The genome of the Altaic Densiovan includes two key genes (ADSL & CBTNAP2) linked with autism in modern human populations. This does not mean that all Denisovans were autistic, but there is good reason to suspect that the Denisovan brain operated in a manner similar to that of modern human individuals displaying savant-like talents. Not only might this explain the Denisovans’ rapid acceleration in early technologies, along with their advanced human behavior, but since isolation is a common trait of autistic people, this may explain why Denisovans, and even the Thunder People, thrived in remote mountainous regions, enduring harsh climates for most of the year.

An autistic mindset might also explain how the Denisovans, as the forerunners of the Thunder People, were able to achieve such a strong mental empathy with creatures of the natural world. This perhaps led to the development both of animism and of shamanism, including the adoption of animal and bird paraphernalia to make a connection with the spirit realms.

Thunderbird Families

The Animiki´ are said to have assumed human form:“by tilting back their beaks like a mask, and by removing their feathers as if it were a feather-covered blanket”.

The World Heritage Encyclopedia adds that there

“…are stories of thunderbirds in human form marrying into human families; some families may trace their lineage to such an event. Families of thunderbirds who kept to themselves but wore human form were said to have lived along the northern tip of Vancouver Island. The story goes that other tribes soon forgot the nature of one of these thunderbird families, and when one tribe tried to take them as slaves, the thunderbirds put on their feather blankets and transformed to take vengeance upon their foolish captors.”

The ‘feather blankets’ in question might better be described as feather garments or animalistic costumes like those worn by shamans. The reference to certain families claiming descent from the Thunder People could even help explain the increased presence of Denisovan DNA among the Ojibwa and Cree. The fact that the Jes´sakkīd´, as the Ojibwa shaman, saw his gift of magic power deriving from the Animiki´, and usually held the bird in the ‘highest position in his estimation’, is significant. Ojibwa illustrations of the Jes´sakkīd´s wigwam-like lodge, called the Jĕs´sakkân´, show the thunderbird directly above the structure’s round smoke hole, while other spirit animals are seen either side of the structure.

Were the Jes´sakkīd´ part of a long lineage that originated with the Denisovans themselves? Is this why these wild shamans remained completely separate from the Ojibwa’s regular priesthood known as the Grand Medicine Society? Were Anishinaabeg descendants of an archaic hybrid population of Denisovan ancestry, remembered in legend as the much-feared Thunder People - giant birds that could shape-shift into human form by removing their ‘feather blankets’? This seems plausible in the knowledge that the Animiki´ could mate with mortal humans and produce offspring.

Giants of Legend

The Denisovan fossils recovered from the Denisova Cave are particularly large in comparison to those of modern human populations, suggesting that at least some Denisovans were of enormous size and stature. Could the Thunder People not only be Denisovan hybrids, but also the giants of legend, whose skeletal remains have been found in Native American mounds across the United States? As attractive as this hypothesis might seem, it is unlikely to be confirmed any time soon, as all skeletal remains of First Peoples held in national institutions and museums within the USA were repatriated at the beginning of the 1990s as part of the NAGPRA law. Until oversized human bones and teeth discovered in a true Native American context are DNA tested, little more can be said on the matter. Having stated this, it does seem possible that the lineal descendants of the Animiki´ or Thunder People of the Great Lakes-St Lawrence River region went on to become the elite of early Native American mound-building cultures such as the Adena, (circa 1000 - 200 BC) as well as the ancestors of indigenous shamanistic groups such as the Jes´sakkīd of Ojibwa tradition. This last idea is backed up by the high level of Denisovan DNA found even today among the Ojibwa and Cree.

Echoes of the Past

In conclusion it seems likely that pronounced, over-sized Denisovan hybrids in North America were remembered in Native American tradition as mythical beings of great size and stature, who possessed supernatural powers such as the ability to control thunder, lightning, storms and rain. Their memory will be attached not only to familiar animistic forms such as thunderbirds, eagles, falcons, vultures, ravens, and snakes, but also to the highest and most primordial mountain shrines and retreats. These might include sites bearing ‘thunder’ or ‘snake’ place-names, as well as locations where extreme weather patterns have long been recorded. The former presence of the Thunder People may be linked also to sites associated with exotic materials traditionally thought to have originated in the sky world. This will include the dark, volcanic glass known as obsidian, which according to the Yuki of California, was hurled to earth from a single large block by a spirit named Milili, who bore the shape of a giant eagle or condor.

Such legends are found everywhere from the American Northwest all the way down to California and Arizona in the south. Where they do exist take note, for they could reveal key information about the sacred places and power spots of the very first peoples to inhabitant the American continent. These unquestionably included the hybrid descendants of the Denisovan populations that thrived in places like the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia down to around 40,000 years ago. All these topics and more feature in an upcoming book by Dr. Gregory Little, an expert on the origins of America’s mound-building cultures, and the present author, titled Denisovan Dawn: Hybrid Origins, Göbekli Tepe and the American Genesis, (release date 2019) published by Inner Traditions International.

Thanks go out to Debbie Cartwright, Russell M. Hossain, Greg Little, Richard Ward, Tim Yearington, and Augustus Frates, for their help during the research and writing of this article.

Andrew Collins is one of the world’s foremost experts on Göbekli Tepe, having first visited the site in 2004. He has been investigating its Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture for over 20 years, and is the author of various books that feature the subject including From the Ashes of Angels (1996), The Cygnus Mystery (2006) and Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods (2014). Path of Souls: The Native American Death Journey (2014 Gregory Little) and The Cygnus Key: The Denisovan Legacy, Göbekli Tepe and the Birth of Egypt. (2018). His website is www.andrewcollins.com.

Top Image: Thunderbird Shaman. (Deriv Liz Leafloor)

References

Collins, A. 2014. The Coming of the Giants: Rise of the Human Hybrids, In Little, 227-239.

Collins, A. 2018. The Cygnus Key: The Denisovan Legacy, Göbekli Tepe, and the Birth of Egypt. Rochester, V.T.: Bear & Co.

Finlayson, C. et al. 2012. Birds of a Feather: Neanderthal Exploitation of Raptors and Corvids. PLOS One 7:10 (September 17, 2012), Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045927.

Gannon, M. 2015. Neanderthals Wore Eagle Talons As Jewelry 130,000 Years Ago. LiveScience (March 11, 2015), Available at: https://www.livescience.com/50114-neanderthals-wore-eagle-talon-jewelry.html.

Hoffman, W. J. 1891. The Midē’Wiwin or ‘Grand Medicine Society’ of the Ojibwa. Seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1885-1886, pages 143-300. Washington D. C.: Government Printing Office.

Huerta-Sánchez, E. et al. 2014. Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA, Nature 512:7513 (August 14, 2014), 194-197.

Jones, W. 1916. Ojibwa Tales from the North Shore of Lake Superior, The Journal of American Folklore 29:113 (July-September 1916), 368-391.

Keys, D. 2018. Prehistoric autism helped produce much of the world’s earliest great art, study says. Independent (May 14, 2018), Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/archaeology/prehistoric-autism-cave-paintings-barry-wright-penny-spikins-university-of-york-a8351751.html.

Lankford, G. E. 2007b. The ‘Path of Souls’: Some Death Imagery in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. In Reilly III and Garber, 174-212.

Little, G, foreword and afterword by Andrew Collins. 2014. Path of Souls: The Native American Death Journey. Memphis, Tenn.: Eagle Wing Books.

Sankararaman, S.; Mallick, S.; Patterson, N. & Reich, D. 2016. The Combined Landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal Ancestry in Present-Day Humans, Current Biology 26:9 (May 9, 2016), 1241–1247.

Let's keep our minds open, for we know so little. The region this subject matter covers is archaic/antique and many cultures have addressed it in so many myths. And now, you've brought science to bear upon the many aspects of the subject matter, with the precision of DNA technology. I'm gladdened beyond description!

What about the Clovis Point Africans that migrated to the Americas in 15,000 BCE ??? They landed on the east coast near present day Savannah, Ga.