The 10 Most Important Human Evolution Discoveries of 2025

The year 2025 has proven to be a landmark period for understanding our ancient past. From revolutionary fossil discoveries to groundbreaking genetic studies, this year’s findings have fundamentally challenged our understanding of human origins, migration patterns, and the complex evolutionary pathways that led to modern humans. Here are the ten most significant human evolution and anthropological discoveries of 2025.

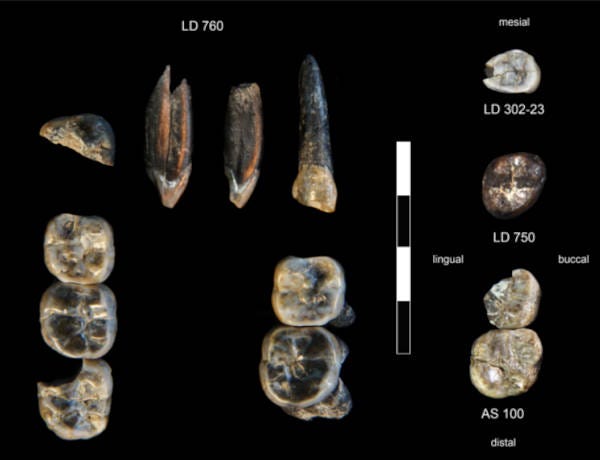

1. New Human Ancestor Species Discovered in Ethiopia

Scientists made a groundbreaking discovery in Ethiopia’s Afar region that revolutionized our understanding of human evolution. The research team, led by Arizona State University, uncovered 13 fossilized teeth belonging to a previously unknown species of Australopithecus that coexisted with the earliest members of our own genus Homo between 2.6 and 2.8 million years ago.

This remarkable finding demonstrates that human evolution was far more complex than traditionally imagined, resembling what researchers describe as a “bushy tree” rather than a straight evolutionary line. The new species was found at the famous Ledi-Geraru Research Project site, where scientists had previously discovered the oldest known Homo specimen and the earliest stone tools on Earth.

“This new research shows that the image many of us have in our minds of an ape to a Neanderthal to a modern human is not correct — evolution doesn’t work like that,” explains Kaye Reed, a research scientist at Arizona State University’s Institute of Human Origins. “Here we have two hominin species that are together. And human evolution is not linear — it’s a bushy tree; there are life forms that go extinct.”

2. Million-Year-Old Chinese Skull Rewrites Human Evolution Timeline

A remarkable million-year-old skull discovered in China has shattered long-held beliefs about when modern humans and their closest relatives diverged from common ancestors. The Yunxian 2 skull, originally excavated in 1990 from Hubei Province, was digitally reconstructed using sophisticated CT imaging techniques, revealing that it belongs to the mysterious Homo longi lineage—closer to Denisovans than to Homo erectus as previously thought.

The research, published in Science, suggests that major human lineages diverged much earlier than previously believed. The Neanderthal clade separated around 1.38 million years ago, followed by the Homo longi clade at 1.2 million years ago, and finally Homo sapiens at 1.02 million years ago. This dramatically compressed timeframe suggests a period of rapid evolutionary diversification.

Perhaps most controversially, the discovery raises fundamental questions about the geographic origins of modern humanity, suggesting that the ancestral population from which all three lineages emerged may have existed in western Asia rather than Africa—potentially challenging the traditional “Out of Africa” model.

3. Lucy May Not Be Our Direct Human Ancestor After All

Revolutionary fossil evidence from Ethiopia is challenging decades of scientific consensus about human origins. New discoveries published in Nature suggest that the famous Lucy fossil, long considered a direct ancestor of modern humans, may instead represent just one branch of a much more complex evolutionary tree.

The breakthrough comes from analysis of the mysterious “Burtele foot,” a 3.4-million-year-old partial foot that retained an opposable big toe designed for grasping tree branches. Recent fieldwork has yielded additional jaw and tooth fossils that link this foot to Australopithecus deyiremeda, a distinct hominin species that lived alongside Lucy’s kind.

Chemical analysis of tooth enamel indicates that A. deyiremeda subsisted primarily on forest foods, contrasting sharply with A. afarensis (Lucy’s species), which consumed a more varied diet. The research suggests that A. deyiremeda may be more closely related to the even older Australopithecus anamensis than to Lucy’s species, undermining the traditional view of A. afarensis as the single ancestral trunk from which all later humans descended.

4. 300,000-Year-Old Teeth Reveal Ancient Humans Interbred with Homo Erectus

Revolutionary 300,000-year-old dental remains from China’s Hualongdong site are rewriting our understanding of human evolution in Asia. The 21 dental elements, including 14 teeth still embedded in a remarkably preserved cranium, display an unprecedented combination of primitive and modern features, suggesting early humans may have interbred with Homo erectus in ways previously thought impossible.

The teeth combine archaic features typical of Homo erectus—such as robust molar and premolar roots—with distinctly modern traits including reduced third molars commonly found in Homo sapiens and smooth buccal surfaces. This unique combination challenges established evolutionary classifications.

“It’s a mosaic of primitive and derived traits never seen before – almost as if the evolutionary clock were ticking at different speeds in different parts of the body,” explained María Martinón-Torres, Director of CENIEH and co-author of the study published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

5. Genetic Study Reveals Hidden Chapter in Human Evolution

Modern humans descended from not one, but at least two ancestral populations that drifted apart and later reconnected, long before modern humans spread across the globe. Using advanced analysis based on full genome sequences, researchers from the University of Cambridge found evidence that two ancient populations diverged around 1.5 million years ago and came back together about 300,000 years ago.

One group contributed 80% of the genetic makeup of modern humans, while the other contributed 20%. Unlike Neanderthal DNA, which makes up roughly 2% of the genome of non-African modern humans, this ancient mixing event contributed as much as 10 times that amount and is found in all modern humans.

“Our research shows clear signs that our evolutionary origins are more complex, involving different groups that developed separately for more than a million years, then came back to form the modern human species,” said co-author Professor Richard Durbin. The study, published in Nature Genetics, suggests that genes inherited from the minority population—particularly those related to brain function and neural processing—may have played a crucial role in human evolution.

6. Greek Petralona Skull Finally Dated: 286,000 Years Old

After decades of controversy, the Petralona skull—one of Europe’s most significant hominin fossils—has been definitively dated to at least 286,000 years old using advanced uranium-series dating techniques. The research, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, settles a long-standing debate and provides crucial evidence that multiple human lineages coexisted in Europe during the Middle Pleistocene period.

Discovered in 1960 in the Petralona Cave in northern Greece, the skull’s age had been disputed for over four decades, with estimates ranging from 170,000 to 700,000 years. The new dating places the Petralona hominin within the Middle Pleistocene period, suggesting it belongs to a population that coexisted with early Neanderthal lineages.

The skull exhibits distinctive features that set it apart from both modern humans and Neanderthals, with its robust cranial structure placing it within the broader category of Homo heidelbergensis. The definitive dating supports growing evidence that Europe hosted multiple human populations during this critical period.

7. 2.2 Million-Year-Old Tooth Pits Shed Light on Human Family Tree

Scientists discovered something remarkable on fossilized teeth lying in African soil for millions of years: tiny, uniform pits grouped in patterns too regular to be coincidental. These shallow punctures, found primarily in back molars, may represent a genetic signature for an entire extinct genus: Paranthropus.

The study, published in The Journal of Human Evolution, found that these uniform, circular, and shallow pits (UCS) occur in a predictable pattern on the chewing surfaces of Paranthropus molars from both eastern and southern Africa. However, the pitting was virtually nonexistent in Homo (our genus) and uncommon in Australopithecus africanus, previously considered to be Paranthropus‘s immediate ancestor.

Lead researcher Ian Towle from Monash University explained that these pits likely have a genetic basis, possibly similar to amelogenesis imperfecta, a genetic disorder affecting tooth enamel in modern humans. The discovery provides a potential taxonomic marker independent of bone morphology or DNA, offering a new tool for identifying and classifying ancient hominin species.

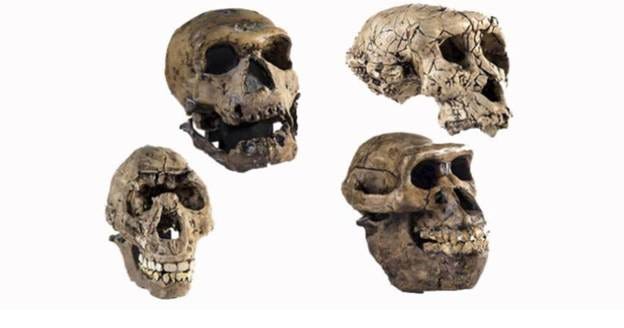

8. Two Species Left Africa Together 1.8 Million Years Ago

New analysis of fossils from Dmanisi, Georgia, suggests that not one, but two distinct ancient human species migrated together from Africa approximately 1.8 million years ago. The research, focused on five skulls discovered between 1999 and 2005, proposes that Homo erectus may have been accompanied by a more primitive hominin species during humanity’s first great exodus from the African continent.

At the heart of this discovery lies Skull 5, which exhibits characteristics dramatically different from its companions. With an exceptionally large jaw and facial structure yet one of the smallest braincase capacities ever found in the Homo genus (approximately 546 cubic centimeters), Skull 5’s primitive features have led researchers to classify it alongside Australopiths rather than with the more advanced Homo erectus specimens found at the same location.

If confirmed, the presence of two distinct hominin species at Dmanisi would fundamentally alter our understanding of early human migration patterns, suggesting that the exodus from Africa may have been a more communal event than previously imagined.

9. Oldest Genetic Data from an Egyptian Reveals Ancient Ancestry

Scientists successfully sequenced the genome of a man buried in Egypt around 4,500 years ago, making him the oldest genome from Egypt to date. The breakthrough study offers rare insight into the genetic ancestry of early Egyptians and reveals links to both ancient north Africa and Mesopotamia.

Despite Egypt’s challenging conditions for DNA preservation—heat and humidity typically destroy genetic material—the research team found that about 4-5% of DNA fragments came from the individual himself, enough to recover meaningful genetic information. The unusual burial inside a ceramic vessel within a rock-cut tomb likely helped shield the remains from damaging elements.

The genetic analysis revealed that about 80% of the man’s ancestry was shared with earlier north African populations, while the remaining 20% was more similar to groups from the eastern Fertile Crescent, particularly Neolithic Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). This genetic profile fits with archaeological evidence of long-standing connections between Egypt and the eastern Fertile Crescent dating back at least 10,000 years.

10. UK Discovery Reveals Earliest Human Fire-Making: 400,000 Years Ago

A groundbreaking archaeological discovery in Suffolk, England, has pushed back the timeline for human-made fire by an astonishing 350,000 years. Researchers excavating at Barnham uncovered compelling evidence that early Neanderthals were creating fire on demand 400,000 years ago—the earliest known instance of deliberate fire-making in human history.

The discovery, published in Nature, contained three crucial pieces of evidence: a preserved hearth with heated sediments, fire-damaged hand axes, and fragments of iron pyrite—the mineral our ancestors used as the world’s first lighter. By striking flint against pyrite, these ancient humans could create sparks hot enough to ignite dry tinder.

What makes the pyrite discovery particularly significant is that this mineral doesn’t occur naturally in the Suffolk area, meaning ancient inhabitants traveled considerable distances to obtain it, understanding its unique fire-making properties. Professor Nick Ashton from the British Museum, who led the excavation, described it as “the most exciting discovery of my 40-year career.”

The ability to create fire on demand had cascading effects on human evolution, providing warmth in harsh climates, protection from predators, expanded food options through cooking, and creating lit spaces that became focal points for social interaction and knowledge transmission—potentially even spurring the development of language itself.

Conclusion

The discoveries of 2025 paint a picture of human evolution that is far more complex, dynamic, and interconnected than previously thought. From multiple species coexisting and interbreeding to sophisticated technologies developed hundreds of thousands of years earlier than expected, these findings remind us that our understanding of human origins continues to evolve with each new discovery.

Rather than a simple linear progression from ape to modern human, we now see a “bushy tree” of evolution - with numerous branches, some leading to dead ends while others merged and interbred, ultimately contributing to the rich genetic and cultural heritage of Homo sapiens. As archaeological techniques improve and new sites are excavated, we can expect even more surprises that will continue to reshape our understanding of where we came from and what makes us human.

By Gary Manners

The late American biochemist, Dr. Duane Gish said: "Evolution is a fairy tale for adults." I totally agree with him. I stopped believing in evolution when my college evolutionary biology professor drew us interesting pictures on the big dry erase board (yes, that was in the 1960s) showing us how a primordial soup got hit by lightning and the first living cell began! I raised my hand and asked where the lightning came. No answer. He kept on drawing and explaining. That was the day I began to question the theory of evolution. It seemed like a fairy to me. Still does. Something does not come from nothing. If you saw a beautiful painting or absolutely fantastic shiny new vehicle you'd want to know who designed or painted it. You'd NEVER assume it just "evolved." So why would people ever look at living creatures and assume they "just evolved" over billions of years. Perhaps given "enough" time anything could just appear. HA And where did water come from? There's definitely a Designer of our world.

Great summary 👍