Swords of Fate: The Ancient Blades That Forged History

For thousands of years humans have found good reason to stab, chop, slice and dice each other up, and the choice weapon which has endured the tests of time is the sword. Historically, kings, emperors, princes and royal army generals all owned their own personal swords, which were most often handed down or manufactured by the ‘greatest sword maker of the land’, and while so much has been written about mythological and legendary swords, less has been written about the real life weapons which changed the shape of warfare and slashed history into shape.

Ancient Origins of Swords

Excavations in ancient Harappan sites in present-day Pakistan have yielded that the world’s oldest copper swords appeared during the Bronze Age. By the Middle Ages iron and steel swords were being mass produced and soldiers were trained in hand to hand combat including swordsmanship. A collection of what are among the earliest swords ever discovered were found in Mesopotamia, dating to the start of the second millennium BC. For example, the Steele of the Vultures carved about 2500 BC shows the Sumerian king, Eannatum, using a sickle-like sword.

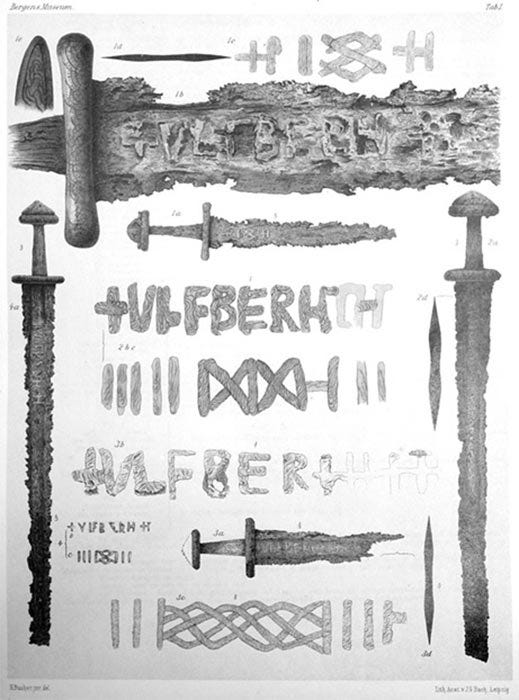

Viking Ulfberht Sword

Viking Ulfberht blades were forged with crucible steel and have the curious inscription ‘VLFBERHT' on the blade. Dated between the ninth and 11th centuries, according to an article on War History, today’s best blacksmiths have had a hard time reproducing this material, which is more superior to what is found in average medieval swords. The sharpness of the blades means wielders could easily cut through bones and lower-quality weapons with one blow, which raises the question, 'How did Viking warriors develop such an advanced sword with such a pure metal that was hundreds of years ahead of the Viking technologies of the time?

The scientists who have tested the swords calculated that crucible steel, with its high carbon content (up to 1.2%) meant it was necessary to have heated the metals to a temperature of 1,600° C. This indicates the Ulfberhts were about 800 years ahead of European methods of achieving such high temperatures, which were not figured out until the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. However, crucible steel was produced in India and Sri Lanka from about 300 BC, and later in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and other Central Asian areas, leading scientists to conclude that the Ulfberht swords might have originated in India.

However, not everyone agrees with this origin story and Anne Stalsberg, of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, Trondheim, Norway and Robert Lehmann, a chemist at the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Hannover, agree in a 2012 research paper that the material from which the sword was made ‘was definitely not supplied from the East’. These two scientists suggest that they had maybe been forged in Austrasia. According to Lehmann the sword contained a large amount of manganese, which refutes the idea that the raw materials had been forged in the East.

Garda, however, was made from iron with a high arsenic content, which is a distinctive European design feature. The handles of the swords were sometimes covered with a layer of tin and lead, which Lehmann determined was mined in the Taunus region north of Frankfurt. Pointing out that during the Middle Ages monasteries in the Taunus region manufactured weapons, Lehman offered a competing origin story to the controversial Indian hypothesis.

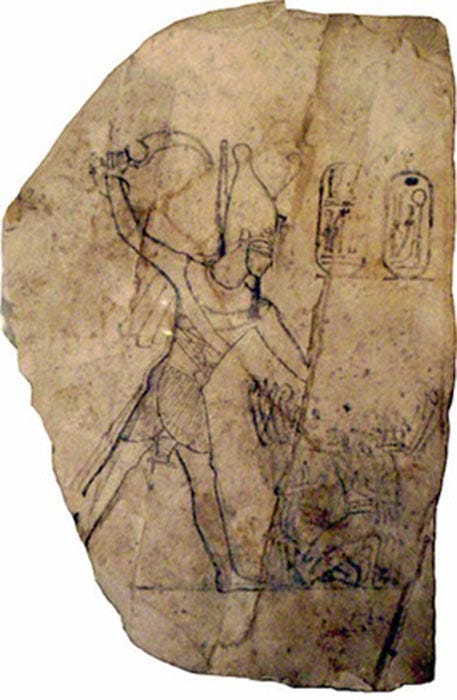

Egyptian Khopesh

The khopesh is a curved sword and its primary uses were cutting, chopping and slashing, but it was useful for thrusting into body armor as the hook is close to the blade’s tip for ripping the enemy’s shield aside. Having evolved from battle axes and farm implements this ancient Egyptian weapon was only sharpened on its outer curved edge. As a powerful symbol of authority, it was included in the burial rituals of several pharaohs including Ramses II and Tutankhamun, who were both entombed with a golden khopesh. The curved khopesh was utilized during the Bronze Age in Egypt and it is an ancient weapon reflecting the classic sword style of North Africa and the Near East.

After its development in Mesopotamia, the khopesh was introduced to Egypt after 1500 BC, around the New Kingdom era, and the early samples of the khopesh have a full tang with a grip fasted with rivets. Later examples feature flanged hilts that have organic inlays including ivory, bone and timber for grips. The blade and hilts of the khopesh are cast in a single piece making the weapon more durable. During the Bronze Age the Egyptian empire used such weapons to repel the Sea People. Unlike the Canaanites, the Egyptian empires developed advanced weapons including the khopesh, which allowed them to maintain their sovereignty and develop their supremacy.

Ancient Greeks adopted the kopis or machaira around the sixth century BC and some scholars argue that the word kopis may have originated from the Egyptian word khopesh. Terrance Wise in his 1981 book Ancient Armies of the Middle East states that eastern and central Africa, the modern Burundi and Rwanda, had daggers that appeared like a sickle, with blades comparable to the khopesh, from which they are thought to have originated. Thus, the khopesh is the forefather of most of the swords wielded in the history of ancient Africa and the Middle East.

Chinese Hooked Swords

Measuring from four to six feet long, ( 1.2 to 1.8 meters) from the top of the hook to the end of the sharpened hilt, Chinese hook swords, or fu tao, hu tou gou (tiger head hook), were originally wielded by the legendary Shoalin monks of northern China. Artfully curved blades form a hook shape at the end which allowed the user to connect the blades by the tips to wield them as single, longer-ranged weapons. Furthermore, the crescent-shaped guards blocked blows and could slash enemies at close range and the ends of the hilts were as sharp as daggers for stabbing. Hook sword skills are taught in schools such as Northern Shaolin and Seven-Star Mantis, and in southern schools such as Choy Lay Fut, and while modern routines for hook swords involve techniques such as linking paired weapons and wielding them as a single long, flexible weapon, most traditional routines are single person techniques.

According to an article in Mandarin Mansion, Chinese hook swords evolved from their military roles and many modern day martial artists still make a living performing shows of martial arts, often with fanciful weapons to draw in crowds, using unhardened tiger head hook sword blades specifically made for exhibition purposes.

German Mercenaries’ Zweihänder

Zweihänder means ‘two hands’ and these brutal chopping weapons were so large that even the biggest swordsmen needed two hands to wield them. According to Ewart Oakeshott’s 2000 book, European Weapons and Armour: From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, the swords were so powerful they could ‘behead up to seven victims with a single stroke’. Weighing up to 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) and measuring at least 1.4 meter (4 feet 7 inches) long, Zweihänder swords had the characteristics of both the polearm and longsword, but their large size and weight gave them increased range and striking power. It was for these reasons this weapon was the choice chopper of the Swiss or German mercenaries, the Landsknechte, representing the final stage in the trend of increasing size that commenced in the 14th century.

During the 1510s and 1520s the ‘Black Band’ of German mercenaries included 2,000 two-handed swordsmen in a total strength of 17,000 men and the Zweihänder-wielders destroyed the enemy’s wooden pike formations, for which they were granted the title of Meister des langen Schwertes (Master of the Long Sword) by the Marx brotherhood. According to German scholar, Greate Pier fan Wûnseradiel, Frisian’s hero Pier Gerlofs Donia wielded a Zweihänder with such skill, strength and efficiency that he managed to behead several people with it in a single blow. The Zweihänder ascribed to him in 2008 has a length of 213 cm (84 inches) and a mass/weight of about 6.6 kg (15 lb) and is currently on display in the Fries Museum.

Kalaripayattu: Art of Wielding the Urumi

Worn like a regular sword, the urumi acts like a whip with two sharp edges and it was invented during India’s Mauryan Dynasty (circa 350-150 BC). Lethal usage of this steel whip requires the same amount of training as with a regular sword, and skills using this weapon where taught to students in Indian martial arts such as Kalaripayattu. The urumi’s hilt was constructed from iron or brass and it has a crossguard and a slender knucklebow. The handle is known as a disc hilt, the pommel has a decorative spike projecting from the center and the blade is fashioned from flexible edged steel measuring three-quarters to one inch in width.

In order for the weapon to be balanced with its user, the blade length ideally matches the wielder's arm span, usually between four to 5.5 feet. Sri Lankan versions of this weapon have up to 32 blades and is typically used as a set of two, one in each hand. According to a 2007 article in The Hundu, Dr. Saravanan states the urumi requires much less strength since the blade, combined with centrifugal force, is sufficient to inflict similar injury, and controlling the momentum of the blade with each swing allows for such techniques as agile maneuvers and long-reaching spins, for fighting against multiple opponents.

Kalarapayattu, the technique of wielding the urumi, is usually taught last, as it is an exceedingly difficult weapon to use. As the urumi functions like a whip, students start by practicing with a piece of cloth, allowing the student to learn the intricate moves of the urumi and reducing the risk of hurting himself / herself.

Unlike conventional swords the urumi is not good for stabbing because of its flexible nature, and this meant warriors had to swing the weapons over and around their heads and their shoulders in wide arcs, in constant motion, thus maintaining the momentum needed to generate the weapon’s slashing power. Creating a defensive ‘bubble’ around its users, its wielders used the weapon to defend from multiple attackers approaching from a number of angles. Perhaps the weapon’s greatest advantage over the traditional sword is that the urumi could curve itself round the edges of shields during combat, slashing around corners.

To quote a man who is estimated to have killed between 800,000 and 1.2 million people with swords: “Whatever possession we gain by our sword cannot be sure or lasting, but the love gained by kindness and moderation is certain and durable.” Alexander the Great. (20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC).

Ashley Cowie is a Scottish historian, author and documentary filmmaker presenting original perspectives on historical problems, in accessible and exciting ways. His books, articles and television shows explore lost cultures and kingdoms, ancient crafts and artifacts, symbols and architecture, myths and legends telling thought-provoking stories which together offer insights into our shared social history. Find more of Ashley’s work at https://historyfuzz.com/

Top Image: A detailed drawing of a Viking age sword from the early ninth century found at Sæbø in the west of Norway. Bergen Museum. (Public Domain)

By Ashley Cowie