Stilicho, Alaric, Attila, and the Changing World of the Ancient Roman Empire

In the late fourth century, a man born of a Roman noblewoman and an East-Germanic Vandal father served as a Roman cavalry officer. Stilicho served Rome with distinction by embracing the Empire and all it stood for, and would go on to become the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. However, this position would not save him from his fate, nor would it stop the fall of the very empire he sought to protect.

Stilicho, Master of the Soldiers

Stilicho got his break early in life when his parents placed him on the roster of the guards of the court, where he perhaps made contact with the future emperor Theodosius. Later, Stilicho served on an imperial delegation to the Sassanid king Shapur III. Once returned from the Sassanid court, he married Theodosius’ niece, Serena and was given the promotion “master of the stable”.

By 385 AD, he was promoted to general and chief of the guard. In 391, Stilicho was promoted to an even higher post as master of both services, the commander and chief of the army, and it was during this time he met Alaric, Visigoth warlord, and they became comrades in battle.

While his promotions are recorded, little is known of his early military career. However, it is with certainty that Stilicho was involved with defeating the pretender Eugenius of the Western Roman Empire and his commander Arbogast in 394.

Afterwards, Stilicho traveled back east ahead of Theodosius, but soon received word that the Theodosius had died suddenly on 17 January 395 AD. The late emperor had favored Stilicho, and had entrusted his sons, Honorius and Arcadius, to his care. The sudden death of the emperor left Stilicho the most powerful man in the empire that did not hold the title emperor.

Even though Stilicho held a tremendous amount of political power, the sons of Theodosius were his rivals and Stilicho was subject to their rule. However, Stilicho’s greatest rival was the ambitious and greedy Flavius Rufinus, commander in chief for the late Emperor’s eldest son, Arcadius.

Friends and Enemies

Honorius (still underage) became Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, and Arcadius was given the Eastern throne in Constantinople. Stilicho acted as a de facto commander of the armies during that time.

It was from there that Arcadius ordered Stilicho to drop what he was doing and send troops to the defense of Constantinople against Alaric’s forces. Stilicho, possibly upset by having to challenge his previous comrade, agreed to the Arcadius’ wishes and sent the troops requested. However, the troops Stilicho sent ended up murdering Arcadius’ commander, Rufinus, the power behind the eastern throne.

With Rufinus out of the way, Stilicho had a new rival to contend with—Eutropius.

While both men agreed to work together in locating, engaging, and defeating Alaric, it would not happen. As both men struggled for power in the empire, one would have to go. That person was Eutropius, who lost his position due to a plot that included an ally of Stilicho in the Eastern Roman Empire in 399.

War and Politics

Even though Stilicho was the leading commander, sharing his services between Eastern and Western Rome, from both foreign and domestic threats, he was very much a political animal.

However, he had spent most of his military life chasing Alaric. Both men had served together and helped crush the usurpation of Eugenius, but soon became rivals as Alaric had broken his treaty with Rome.

In 397 AD, Stilicho had a chance to engage and defeat Alaric but decided to negotiate a settlement with him instead. It is suspected that Stilicho decided that it would be best to unleash the Gothic king on the Eastern Roman Empire and to bother Stilicho’s rival at the time, Eutropius. This allowed Stilicho to concentrate his time on the Western Roman Empire. However, after four years had passed, Alaric led his army into Italy while Stilicho was away on campaign against other barbarians.

Stilicho, receiving word of Alaric’s invasion, quickly moved his forces back to Italy in 402 AD, and sent word to Britain and the Rhine frontier to send reinforcements to protect Italy. On Easter 402 AD, Stilicho, with Vandal and Alan (Iranian nomads) confederate forces, gave orders to attack Alaric as the Visigoths celebrated, which resulted in victory.

Later that summer, Stilicho inflicted another defeat upon Alaric, and yet once again allowed him to live. Five years later Alaric again invaded the Western Empire and again, Stilicho was away, facing other threatening issues. Stilicho attempted and failed to reach an agreement to stave off Alaric. Besides Alaric, Stilicho faced many challenges elsewhere.

Besides defeating unruly Romans in Africa, he made new treaties with the Franks and Alemanni, and deposed a Frankish king he did not trust.

Another great difficulty he faced was the invasion of the Ostrogoths under the leadership of Radagaisus in 405 A.D. This barbarian invasion eventually led to Stilicho’s downfall, for this would not have happened had he not pulled troops from the Rhine frontier to protect Italy. Even though he did defeat the invaders near Florence in the summer of 406 AD, he still was unable to defeat Radagaisus, and because of this, Radagaisus would remain a threat to Italy for the next several years.

While Stilicho is busy patching up the holes within the Western Empire, Emperor Arcadius died, and Alaric returned. Competition over the throne ensued between Stilicho and Honorius. However, Stilicho’s bid for the throne would fall short. Even though he had won many battles, he never won the war over Radagaisus nor Alaric, and because of this, imperial territory was lost. As such, Emperor Honorius lost confidence in Stilicho and order for his arrest.

History tends to pain Stilicho as a power hungry general who defeated his enemies but let them go in order to manufacture future problems in order to drum up business – in essence, a war racketeer. While this is plausible, another reason to consider why he seems unable to defend the Western Roman Empire effectively is due to the Roman senate.

The senate many times denied Stilicho the resources needed to defend the empire, such as troops and money, but at the same time senators did not like the fact that he was forced to recruit barbarians from tribes he had defeated in battle, whose motives and allegiances were questionable. It was a no-win situation.

As well, it was rumored Stilicho had planned the earlier assassination of his rival, Flavius Rufinus, and plotted to have his own son in line for the throne after Emperor Arcadius died in 408.

Because of this, the senate quickly grew to despise the man who saved Rome multiple times.

Stilicho was executed on August 22, 408, and so was his son Eucherius, shortly thereafter.

The Beginning of the End of the Empire

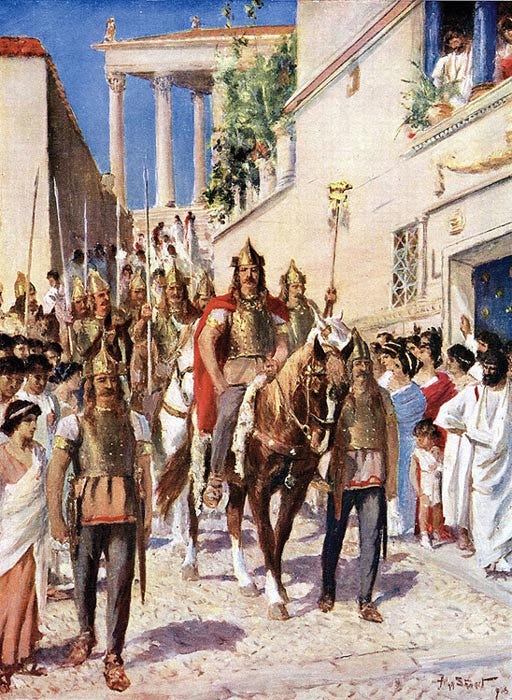

With Stilicho dead, Alaric took advantage of the situation and marched on Rome. On 24 August 410, Alaric and his army were outside the eternal city, when a Roman noblewoman, according to tradition, opened the gates of Rome to the victors.

For three days Alaric’s men plundered and burned the city; it was the first time that Rome had been sacked since the Celts 800 years earlier. According to St. Jerome, “The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken.” Other writers would mention how bad the looting and burning of Rome was. However, this may not be the case.

While there is no doubt the fall of Rome to outsiders caused a great, shocking uproar, the fact of the matter is Alaric was no barbarian. He had allegedly given specific orders to his troops to limit the bloodshed, make few fires, and even though they were allowed to plunder, the men showed great restraint. Overall, it was a unique sacking of a city, especially when the invading Goths and citizens of Rome united and paraded down the streets and celebrated with a sacred plate of the Apostles Peter and Paul.

In the end, Alaric began organizing a naval expedition to Africa but fell ill and died before he could leave.

The sacking of Rome in 410 is considered the defining moment in the gradual collapse of the Western Roman Empire. However, consider that the collapse may have begun seven years earlier, when Stilicho pulled Roman troops who protected the Rhine frontier to defend Italy. Three years later, the Vandals, Suevi, and Alans crossed the Rhine into Gaul, and ultimately collapsed the Roman province of Germania inferior. With Germania inferior under Germanic control, and the psychological impact caused by Alaric’s sacking of Rome—besides losing a portion of North Africa to the Vandals by 439 which effectively ended Rome’s rule over the Western Mediterranean, and along with the internal power struggles—what else could go wrong for the Western Empire? The answer was, the Huns.

Attila, Scourge of God

Attila, the scourge of God, was a mighty warrior who threatened both Roman Empires and much more.

However, Attila never was a direct threat to either Empire. In other words, Attila’s grand future scheme was never to establish an empire, unlike Genghis Khan eight hundred years later. Attila and his Huns’ desires were the ample resources of wealthy neighbors.

Attila was not the first Hun to extract money from the Romans using threatening measures. His uncle, Ruga, was the first to do so in the 420’s. Ruga’s power was such that the Eastern Roman Empire signed a treaty with him, in which he received tribute and the return of Huns who had deserted. When Ruga died, Attila took over and went on the offensive, which led to a new treaty between the two empires.

The Treaty of Margus ensured that Attila would receive not 350 pounds of gold a year but 700 pounds a year. With the Eastern Empire under his thumb, Attila expanded his empire to the north and east of him. All was going well between Attila and Emperor Theodosius II (called Theodosius the Younger), son of Emperor Arcadius until the latter decided not to pay the Huns—a big mistake.

Attila received word that the armies of Theodosius were bogged down in a war against the Sassanids (an Iranian empire). Attila quickly took advantage and invaded the Eastern Empire. The Huns razed a number of important cities, such as Naissus, Singidunum, and Serdice. The sacking, killing and razing of the various cities was so horrible that it was said the stench of death kept many out of the cities and the bones of the dead are to have filled the Danube River.

Attila’s impact was so great that he threatened Constantinople, the very city that fed him. To end his aggression, a new treaty was agreed upon, but this time Attila was given a one-time payment of 6,000 pounds of gold to cover missed payments, and was paid 2,100 pounds of gold a year from there onwards. However, the Huns were dogged by plague, making them weak and unable to react as they had beforehand. Theodosius decided to halt any further payments.

Attila murdered his own brother Bleda for sole power and took to the offensive once again, invading the Eastern Empire and causing even greater damage and, most importantly, got his payments renewed.

It could not have come to a better time for Theodosius, when Justa Grata Honoria, the older sister of Emperor Valentinian III of the Western Roman Empire, sent a message to Attila, offering her hand in marriage and the Western Empire as her dowry.

The end of the west was about complete. With this proposal, the Eastern Empire was now out of mind. Theodosius could not have been happier, but would soon die in a riding accident. His sister Pulcheria married Marcian, which made him emperor. Marcian’s first order of business in dealing with the Huns was to stop paying tribute. By refusing Attila further payments, he provoked him to launch an attack on the fragile Western Empire.

Attila began preparing for the coming campaign. The troops accounted for are said to have numbered between 300,000 to 700,000. However, this may be overestimated. In any case, the size of the force he led into Gaul was of substantial size. Moreover, the army was one of tribes, not just of Huns, but also Alans, Burgundians, Heruls, Ostrogoths, Ripuarians, Franks, Sarmations, Suevi, and Vandals.

Opposing Attila’s mighty force were the Romans, Burgundians, Celts, Salians, Franks, and Visigoths, led by the Roman commander Aetius. Once Attila entered Gaul, he did what he normally does and that was to sack the cities of Rheims, Metz, Strasbourg, Cologne, and Trier. On 20 June 451, the two armies clashed on the plains between Troyes and Chalons. The battle proved to be a decisive victory for the Romans and their allies but at a great cost. According to Jordanes, 165,000 men died that day, including Theodoric the Visigoth who put up a heroic resistance to the Huns.

After Chalons in 452 AD, Attila gathered his forces and made his way into Italy, sacking the cities of Padua, Mantua, Vicenza, Verona, Brescia, Bergamo, and Milan. The Romans were pushed aside by the vast Hunnic army and even Aetius had no troops in Italy substantial enough to put up a resistance nor any he could pull from in Gaul, and so Aetius ultimately lost his auctoritas (authority).

As the story goes Pope Leo I stopped Attila from crossing the Mincius (Mincio) a tributary of the Padus (Po) and persuaded Attila to turn back or face the wrath of God. However, it did not end like that at all. Instead, Pope Leo did arrive but so did two senators by the name of Trygetius, a diplomat who negotiated a deal with Gaiseric years back, and the wealthy Avienus. After much deliberation, Attila agreed to the deal. The Hun ruler agreed to withdraw his forces to later on hand over Honoria and her dowry in wealth. In other words, Valentinian was handing over the empire to Attila.

While Attila waited for Honoria to arrive, he took another woman to marry. As the story goes, one night after excessive drinking, Attila was found the next day, dead in his bed, with his scared bride at his side.

The Western Roman Empire died with Attila. With Attila alive the Western Empire had a reason to exist and that was to feed Attila wealth. With Attila dead, there was no reason in keeping the Western Empire together and even the Eastern Empire understood this as well for they also understood that they could not save the west alone.

Another important point to make before this is finished, is that the Western Roman Empire did not fall to the ‘barbarians’ migrating into the Empire. Instead, they provided Rome the labor needed to farm, the officials to help govern, and the men to fulfill the ranks of the armies. Like most immigrants or migrants, they usually headed for places that presented opportunity or in search to find if such a place exists. While some saw opportunity by use of force, many more saw opportunity through peace and cooperation with their new neighbors.

Rome did not fall to barbarians, Rome fell because the “political means” or through coercion, outweighed the “economic means” through peaceful trade. Even though the Western Roman Empire had disappeared by 476 AD, it would soon be replaced by the peoples they conquered, mixed with the peoples who sought new opportunity, and in doing so, built new kingdoms which eventually became the nations we know today, making up the landscape of Western Europe.

Featured image: Deriv; Stilicho, Alaric, and Attila.

By Cam Rea

References

Burns, Thomas S. Barbarians Within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, Ca. 375-425 A.D. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Bury, J. B. The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians. New York: Russell & Russell, 1963.

Christie, Neil. From Constantine to Charlemagne: An Archaeology of Italy, AD 300-800. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate, 2006.

Cyprian, and Rose Bernard Donna. Letters (1-81). Washington: Catholic University of American Press, 1965.

Dinçer, O. Bahadir, Mehmet Güçer, Sema Karaca, The Struggle For Life Between Borders: Syrian Refugees Fieldwork. International Strategic Research Organization (USAK), 2013.

Elton, Hugh. Warfare in Roman Europe, AD 350-425. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Fields, Nic, and Steve Noon. Attila the Hun: Leadership, Strategy, Conflict. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2014.

Gibbon, Edward, and David Womersley. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. London: Penguin, 2000.

Green, Dennis Howard. Language and History in the early Germanic world. Cambridge: Cambridge university press, 1998.

Heather, P. J. Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Heather, Peter. Fall of the Roman Empire A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Cary: Oxford University Press, USA, 2014.

Hughes, Ian. Stilicho: The Vandal Who Saved Rome. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2010.

James, Edward. Europe’s Barbarians, AD 200-600. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman, 2009.

Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin. The Later Roman Empire, 284-602: A Social Economic and Administrative Survey. Volume I Volume I. Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1964.

Kim, Hyun Jin. The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Maas, Michael. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Mirkovic?, Miroslava. The Later Roman Colonate and Freedom. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997.

Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Europe, AD 400-600. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1975.

Randers-Pehrson, Justine Davis. Barbarians and Romans: The Birth Struggle of Europe, A.D. 400-700. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983.

Thompson, E. A. Romans and Barbarians: The Decline of the Western Empire. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982.

Williams, Derek. Romans and Barbarians: Four Views from the Empire’s Edge, 1st Century A.D. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

Wolfram, Herwig. The Roman Empire and its Germanic peoples. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 1997.

Ok. So migrants good. Gotcha…