Old Symbols, New Feelings

How Did the Cup of Ptolemies Become a Chalice of Christ?

It is always interesting to see how ancient traditions persist even up to the modern era. Whether it is the resurgence of Eastern meditation practices in modern healthcare or the lingering presence of the Christmas tree in the living room, many customs have been co-opted from their original surroundings into a wholly different setting. Not only is this practice nothing new, it is oftentimes done purposefully. With regards to the Christian appropriation of non-Christian (i.e. pagan) cultural elements, the process is called Interpretation christiana, and a great example of it can be seen in the history of how the Cup of Ptolemies became a Chalice of Christ.

The Christian Chalice

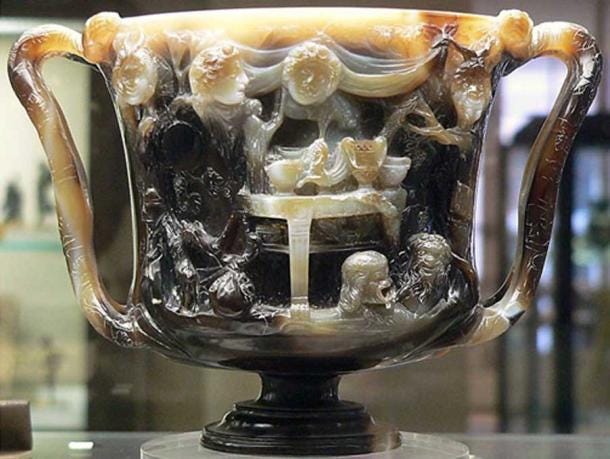

Before it was stolen from the Louvre in 1804, the Cup of Ptolemies had served for hundreds of years as the Eucharistic chalice for the communion wine at the Basilica of St. Denis in northern Paris. The lost artifact was eventually recovered later in the 19th century, but by then it could no longer serve as a chalice. The cup itself is an intricately carved piece of onyx with two handles and measures 3.3 x 4.9 inches (8.4 x 12.5 cm). The cup has a small nub on the bottom, on which it can stand, but was presumably lifted using the handles.

Rosetta-style engraving lauding Cleopatra I and two Ptolemaic Pharaohs unearthed in Egypt

What Happened to Grand Temple Building in Ancient Egypt after the Death of Alexander the Great?

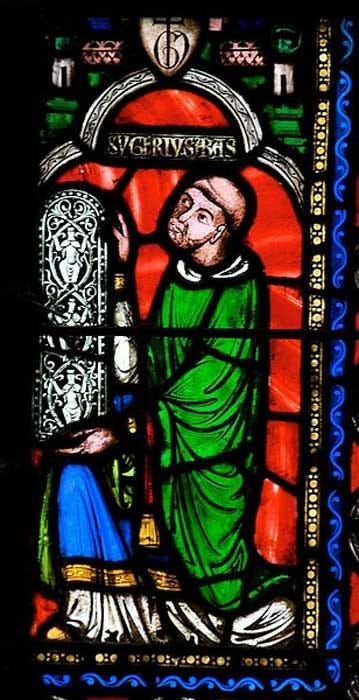

That, at least, is how its pagan creators intended it to be used. Sometime around the Carolinian Renaissance (ushered in by Charlemagne and lasting from the 8th to 9th century), a cone-shaped base was added to the cup to make it a proper chalice. Later, in the 12th century, the famous Abbot Sugar of St. Denis embellished it with gold and precious stones so that the chalice base would be as fantastic as the onyx cup. We know this only from sketches made of the artifact, particularly the engravings made by Michel Félibien in 1706. The chalice’s base was not recovered with the cup (but the thieves were caught in Holland). The French police believe it was broken off and melted down so that the gold and jewels could be better sold. The market for onyx was apparently less accessible.

Declaring the Cup a Chalice for Christ

Félibien’s engraving suggests that on the base of the chalice there was “a two-line inscription in Latin… which reads: hoc vas Xpe tibi [devota] mente dicavit tertius in Francos [sublimis] regmine Karlus . In English, this means: "The [exalted] Charles III, on the French throne, consecrated this vessel for you, Christ, with a [faithful] mind” (Klimczak, 2016).

Now, the Charles III being referred to is a matter of dispute. The most likely candidate is Charles the Bald (reigned from 840-877 AD) but it could also refer to Charlemagne (reigned from 768-814 AD) or Charles the Simple (reigned from 919-923 AD). More important, however, is the conscious acknowledgement that this chalice is being converted from its original purposes in order to become a vessel for Christ.

New Revelations Reignite Debate About Owner of the Lavish Amphipolis Tomb

Armillary Spheres: Following Celestial Objects in the Ancient World

What Treasures Were Lost in the Destruction of the Great Musaeum of Alexandria?

The Chalice’s Blend of Greek/Egyptian Origins

The exact origin date of the Cup of Ptolemies is difficult to determine because there are no similar artifacts with which to compare the craftsmanship. It was most likely made in Alexandria, Egypt during the Hellenistic period sometime between 250 BC – 100 AD. The Ptolemies were a dynasty that ruled over Egypt, Nubia, and Syria from 323 BC to 30 BC. The dynasty started with Ptolemy I (a close companion of Alexander the Great when the Alexandrian empire was divided) and it ended with the suicide of Cleopatra.

The chalice’s name derives from a description written in 1644 by the historian Jean Tristan of Saint-Amant, in which he says the cup was made for the funeral of Ptolemy II: “this vase was made by the command of Ptolemy Philadelphe [Ptolemy II], King of Egypt, and that everything that can be seen represented on it is one of those holidays or sacrifices celebrated in honor of Bacchus, who was so particularly esteemed by the Egyptians” (Vadnal, 2006). There is no evidence to support this claim, but the name stuck.

Jean Tristan of Saint-Amant’s description does, however, provide a neat explanation to a historic anachronism: why would a cup made in Egypt be decorated with symbols of Greek gods? His explanation was that the Egyptians were crazy about Bacchus (the Roman name for the Greek Dionysus, the god of wine). But today scholars believe that the cup was carved by a Greek or Roman, though possibly one working in the great Egyptian city of Alexandria.

The masterfully carved cup depicts classic Dionysian scenes and symbols. One side of the cup, believed to be the front, shows six masks surrounding a sacrificial altar that is supported by two sphinxes (a Greek symbol as well as an Egyptian one). Near the handle, Hermes can be seen hanging up a mask and the raven of Apollo (both Dionysus’ brothers). There are also goats, a cheetah/leopard, and a snake emerging from a wicker basket – all of which are important symbols in the cult of Dionysius. On the other side of the cup, the back side, there is another sacrificial altar, this one showing five (presumably) sacred vessels on top as well as a little female figure carrying a torch, perhaps one of the priestess of the cult. There are also more goats and images of Pan.

‘Un-naming’ the Chalice’s Origins

The cup clearly was an elaborate celebration of the cult of Dionysus and may have been used in its rituals. But the cup’s original purpose and much of the symbolic meanings have been long forgotten. When the Dionysian cup became a Christian chalice, descriptions omitted the Greek symbolism and just declared that there were many pretty animals, trees, and faces. This is an important aspect of Interpretation christiana : ‘un-naming’ - the deliberate omission of traditional interpretations so that they may become forgotten and thus destroyed.

If the origins of the cup are difficult to deduce, how it got into the hands of the French kings is nearly impossible to determine. One king or another eventually donated it to the medieval abbey of St. Denis, who in turn donated it to the Louvre in 1791. Today the cup/chalice is on display in the Cabinet des Médailles at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. It is considered to be one of their greatest treasures.

Top Image: What is now considered the front view of the Cup of the Ptolemies, a Pagan cup turned into a Christian chalice. Source: Clio20/ CC BY SA 3.0

References

Klimczak, Natalia. "Getting to the Bottom of the Captivating Cup of the Ptolemies." Ancient Origins . Ancient Origins, 9 Feb. 2016.

Available at: http://www.ancient-origins.net/artifacts-other-artifacts/getting-bottom-captivating-cup-ptolemies-005322

Vadnal, Jane. "Medieval Art: Treasures of Saint Denis: Cup of the Ptolemys." Medieval Art: Treasures of Saint Denis: Cup of the Ptolemys . University of Pittsburgh, 29 Nov. 2006.

Available at: http://www.medart.pitt.edu/image/France/St-denis/felebien/FelePl4/PlateIV-f.html