New Wonders from Ancient Civilizations: From Mesopotamia to the Etruscan Tombs

Ancient Origins Unleashed Debrief

Greetings the Unleashed!

It sometimes blows my mind a bit when I see what is going on in the other areas in Ancient Origins. I get pretty caught up on the focus of my daily work, which is basically finding all the important and interesting history and archaeology news I can and bringing it to our readers. Then I see what some of the other departments of Ancient Origins are getting up to, and I think, WOW.

So let me share with you what has got me excited today.

Rome, what a city, a historic delight around every corner. Athens delivers the edifices of the gods. The Egyptian pyramids and Sphinx pretty much speak for themselves. Petra just makes you shrink in the presence of the civilization that created it. And Gobekli Tepe…well, just about the oldest manmade spot you can find on the planet.

All fantastic historic locations where you can bathe yourself in the histories you’ve read over the years. All relatively easy to get to. All incredibly touristy. So, what else is there? How do you escape the crowds and find fantastic historic locations to explore?

Well, there’s a whole historic region just a few (admittedly, pretty large) steps east of these that was just as seminal in the development of the world. No prizes for guessing where I am talking about. Mesopotamia. This was the home of some of the most ancient civilizations - Sumerians, Babylonians, Achaemenids, Assyrians. But hardly anyone talks about visiting their great places…Why?

Once you throw the names Iraq, Baghdad, Syria into the equation, your average wannabe intrepid explorer gets a tad nervous. They soon realize no one would be crazy enough to visit there.

These are places of huge historic importance, that are dismissed and neglected by most travelers because they seem a bit risky. Safer perhaps, to join the entrance queues and wait your turn at the photo spot of the better known and well developed attractions.

But crazily enough, there are people daring to visit these neglected spots. I guess it’s the difference between tourist and explorer mentalities. This group of explorers includes some of my colleagues at Ancient Origins. And it turns out, the idea isn’t that crazy.

It is now very feasible to venture to these less visited places. The Mesopotamian strongholds of Eridu, Lagash, Uruk, Ur and Babylon are back on the travel list, and all will be visited this October by the intrepid Ancient Origins Tours team and an experienced specialist tour company.

You can join them…

And now, to the Editor’s choice…

Talking of Mesopotamia…

Parthian Fortress in Iraq May be a Sanctuary for Goddess Anahita

At the remote, ancient mountain fortress of Rabana-Merquly in Iraqi Kurdistan, German archaeologists have made a surprising discovery. Evidence has emerged that suggests the site had been used as a religious sanctuary in the first and second centuries BC, by settlers associated with the legendary Parthian Empire.

Researchers have concluded that a shrine found there had most likely been devoted to the ancient Persian water goddess Anahita, a popular deity from the Zoroastrian religion who was revered by the Parthians.

The excavations that produced the startling new information were led by Dr. Michael Brown, an archaeologist from the Institute of Prehistory, Protohistory and Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology at Heidelberg University in Germany and were supervised by the Iraqi Kurdistan Directorate of Antiquities. The German archaeological team has just published the results of their study in the historical journal Iraq, detailing a find that helps clarify the rich history of the cult of Anahita, which was wildly popular in Mesopotamian lands in the latter half of the first millennium BC.

Among their many fascinating discoveries at the site of the fortress complex, Dr. Brown and his team uncovered what appears to have been a fire altar or shrine, located adjacent to a natural waterfall. Typically, such an altar would have been used to burn oil or make offerings to the deity to which it was dedicated.

Sick like an Egyptian…

Here’s How We Know Life in Ancient Egypt was Ravaged by Disease

The mention of ancient Egypt usually conjures images of colossal pyramids and precious, golden tombs.

But as with most civilizations, the invisible world of infectious disease underpinned life and death along the Nile. In fact, fear of disease was so pervasive it influenced social and religious customs. It even featured in the statues, monuments and graves of the Kingdom of the Pharaohs.

By studying ancient specimens and artifacts, scientists are uncovering how disease rocked this ancient culture.

The most direct evidence of epidemics in ancient Egypt comes from skeletal and DNA evidence obtained from the mummies themselves.

For instance, DNA recovered from the mummy of the boy pharaoh Tutankhamun (1332–1323 BC) led to the discovery he suffered from malaria, along with several other New Kingdom mummies (circa 1800 BC).

In other examples:

skeletal and DNA evidence found in the city of Abydos suggests one in four people may have had tuberculosis

the mummy of Ramesses V (circa 1149–1145 BC) has scars indicating smallpox

the wives of Mentuhotep II (circa 2000 BC) were buried hastily in a “mass grave”, suggesting a pandemic had occurred

and the mummies of two pharaohs, Siptah (1197–1191 BC) and Khnum-Nekht (circa 1800 BC), were found with the deformed equinus foot which is characteristic of the viral disease polio.

Amenhotep III was the ninth pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, and ruled from about 1388–1351 BC.

There are several reasons experts think his reign was marked by a devastating disease outbreak. For instance, two separate carvings from this time depict a priest and a royal couple with the polio dropped-foot.

It’s a beauty…

Magnet Fisher Drags 1,200-Year-Old Viking Sword from English River

In a remarkable find, an artifact of significant historical importance has been recovered by an avid magnet fisherman. Trevor Penny was scouring the River Cherwell near Enslow in Oxfordshire, expecting to unearth nothing more than the usual assortment of metallic detritus. However, fate had something far more extraordinary in store for him. With a tug and a pull, his magnet clung not to the usual scrap metal but to a relic of the distant past—a Viking sword dating back 1,200 years! His magnet had attracted a substantial relic from the past—a sword that, to his astonishment, has been confirmed as a Viking weapon dating back around 1,200 years to around 850 AD.

While exploring the river's depths in November, Penny happened upon this remarkable piece of history. Initially obscured by years of corrosion and sediment, the sword's true identity was revealed through the concerted efforts of Penny and local archaeological experts.

“It really did feel quite amazing – it’s the oldest thing found in this county magnet fishing”, Penny commented, reflecting on the journey from discovery to verification, recorded the Oxford Mail.

The confirmation of the sword's origins catapults this find into the limelight, shedding new light on the tumultuous period when England was a battleground for control between the Anglo-Saxon occupiers and the invading Danish Vikings. This era was marked by significant unrest and pivotal battles, including the Viking raid near Plymouth and their subsequent defeat by Anglo-Saxon forces under King Aethelwulf of Wessex and his son Æthelstan of Kent.

Kept in clay…

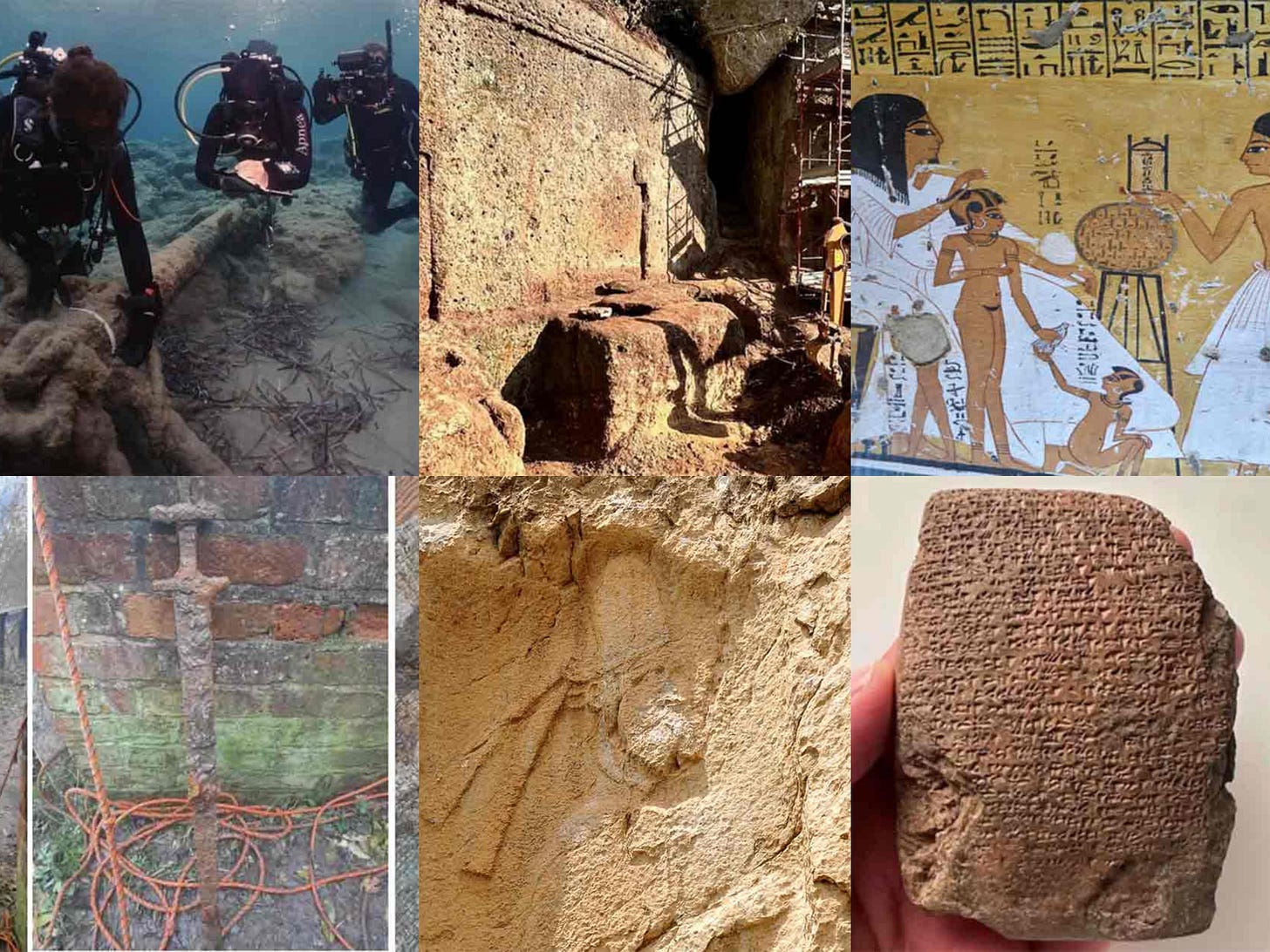

Clay Tablet From 3,300-Years Ago Tells Story of the Siege and Plunder of Four Hittite Cities

A 3,300-year-old clay tablet unearthed in central Turkey has painted a tale of a devastating foreign invasion of the Hittite Empire during a period of internal strife and civil war. As the civil war played out, the invasion allegedly supported one of the warring factions, as deciphered from the tablet's cuneiform script. Discovered in summer 2023, the palm-sized tablet was found amidst the ruins of Büklükale, situated approximately 37 miles (60km) southeast of Ankara, Turkey's capital.

Previously, only broken clay tablets and the like were unearthed at Büklükale, but this is the first complete tablet in near perfect condition. It had been discovered by archaeologist Kimiyoshi Matsumura of the Japanese Institute of Anatolian Archaeology in May 2023. The Hittite utilization of the Hurrian language in religious contexts suggests that the tablet serves as a historical record documenting a sacred rite performed by the Hittite monarch, reports Live Science.

Büklükale was thought to be a major Hittite city by archaeologists, but with this new discovery, potentially a royal residence on par with the Hittite capital, Hattusa, located some 70 miles (112km) to the northeast.

As per the translation by Mark Weeden, an associate professor specializing in ancient Middle Eastern languages at University College London, the initial six lines of cuneiform text on the tablet, inscribed in the Hittite language, lament the dire state of "four cities, including the capital, Hattusa," indicating a calamitous event. The subsequent 64 lines are composed in the Hurrian language, constituting a prayer seeking divine assistance for victory.

"The find of the Hurrian tablet means that the religious ritual at Büklükale was performed by the Hittite king," Weeden told Live Science. "It indicates that, at the least, the Hittite king came to Büklükale … and performed the ritual."

The Hurrian language, originally associated with the Mitanni kingdom in the region, eventually became utilized by the Hittite Empire in some sort of a subordinate capacity. Despite ongoing scholarly efforts, Hurrian remains a language of which we have limited understanding. Matsumura explained that experts have dedicated several months to deciphering the inscription's meaning.

It’s around here somewhere…

Huge Etruscan Tomb Found Hidden in Plain Sight at San Giuliano Necropolis

The world’s most expansive and complex Etruscan necropolis continues to produce surprises, revealing more details about the powerful civilization that preceded the Romans as the dominant force in ancient Italy. While performing maintenance procedures at the San Giuliano Necropolis in Marturanum Park in the central Italian village of Barbarano Romano, archaeologists unearthed a beautifully preserved Etruscan tomb, one that had somehow remained undetected and undiscovered for decades.

The discovery of the tomb was announced by the Superintendency of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the Province of Viterbo and Southern Etruria on its Facebook page. It introduced the newly identified rock-carved structure as “an additional three-room tomb over headed by three semi-finished doors … perfectly preserved in the architectural part.”

The newly discovered tomb was found quite close to the Queen’s Tomb (Tomba della Regina), a monumental Etruscan installation that dates to the fifth century BC. This huge man-made, rock-cut cavern is approximately 45 feet (14 meters) wide and 33 feet (10 meters) high, and includes stairs leading to an upper terrace, plus two doorways that open into a pair of interior burial chambers. The new tomb was cut out of the rock right next to it, and it is quite astonishing that it was overlooked for so long.

The archaeologists responsible for the newly discovered tomb were digging and cleaning around the Queen’s Tomb as part of a restoration project, and they were not really looking for anything new. But much to their surprise, as they continued clearing away overgrown vegetation from the outside of the Queen’s Tomb they noticed the unmistakable outline of another tomb, one that was apparently constructed parallel to the Tomba della Regina. Once they’d uncovered it and opened it there was no longer any doubt about what they had discovered, totally by accident.

The new tomb essentially matches the Queen’s Tomb in size and shape, making it clear it was built according to the same template. This means it was likely constructed at nearly the same time as its neighboring tomb, in the fourth century BC.

“This operation is thus proving to be fundamental to shed light on a part of necropolis previously unclear and that will increase knowledge of the varieties of tombs of the 5th and 4th centuries BC,” the Superintendency wrote in its Facebook post.

Despite its highbrow name, archaeologists don’t believe the Queen’s Tomb was used for elite burials. It and its newly discovered partner instead appear to have been reserved for the entombment of people who belonged to the Etruscan version of the middle class.

Ships ahoy…

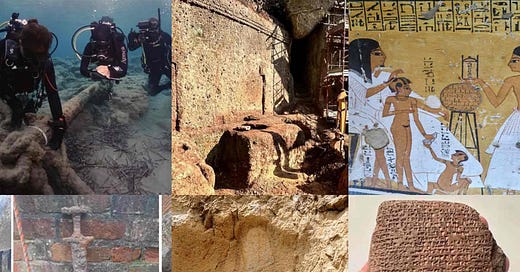

Ten Shipwrecks Spanning 5,000 Years of History Spotted off Kasos Island

Underwater archaeologists exploring the sea bottom off the beaches of Greece’s Kasos Island discovered something not entirely unexpected, but still quite surprising. Over the course of four years of exploration, they spotted and identified ruins and artifacts from approximately 10 different shipwrecks, with one dating back as far as 3,000 BC.

While they may have been looking for the remains of lost ships, the archaeologists never expected to discover such an impressive bounty of maritime wreckage and beautifully preserved objects. These finds will be invaluable to scientists and academics seeking to learn more about the history of commercial shipping in the southern Aegean and Mediterranean seas in ancient times, and among other things they reveal the true nature of the dangers associated with sea travel in the region throughout history.

The explorations that produced this remarkable result were launched under the auspices of the Kasos Maritime Archaeological Project, which began in 2019 and concluded in October 2023. The Greek Ministry of Culture and the country’s National Hellenic Research Foundation jointly sponsored this ambitious initiative, which was specifically designed to detect ancient and/or modern shipwrecks and identify their origin and cargoes.

Til next time…to tour or to explore, that is the question.

Gary Manners - Senior Editor, Ancient Origins