Cult Worship at the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia

The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia is a religious complex from the time of the Roman Republic. This ancient sanctuary is situated in Praeneste (known today as Palestrina), not far from Rome. The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia was famed for its oracular cult, and remained active until the late 4th century AD. The sanctuary lost its religious function in the centuries that followed, and a town was built over its ruins during the Middle Ages. It was only after the Second World War that the ancient monument was visible once more, as much of the town had been destroyed by Allied bombings. Today, the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia is a tourist destination.

Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia: Dedicated Goddess Fortuna Primigenia

As its name suggests, the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia was dedicated to the goddess Fortuna Primigenia whose name may be translated to mean ‘Fortune of the First Born.’ Alternatively, the word ‘Primigenia’ may be taken to mean ‘Primordial’ or ‘Original’, a reference to the antiquity of her cult. Yet another interpretation of the goddess’ name is ‘First-Bearer’, meaning that she was the first to bear children. According to Cicero, the goddess is depicted as suckling two infants, one Jupiter, and the other Juno. Cicero goes on to say that the goddess was especially popular amongst mothers. Fortuna Primigenia was also worshipped as a goddess of fate and luck and was believed to be responsible for fixing the destiny of newborns.

Fortuna Primigenia was initially considered to be a foreign goddess by the Romans, as her center of worship was Praeneste, located about 37 km (23 mi.) southeast of Rome. Situated on a spur of the Apennines Mountains, Praeneste is one of the most ancient towns of Latium. In ancient times, Praeneste was also one of Latium’s most important and powerful settlements, and came into conflict with Rome on many occasions. During the Latin War, which lasted from 340 to 338 BC, Praeneste was defeated, lost part of its territory, and became an ally of Rome. In 215 BC, for example, soldiers from Praeneste were defending, albeit unsuccessfully, Casilinum, a town in Campania, from the Carthaginians who were led by Hannibal. Although the surviving defenders were offered Roman citizenship, they refused the offer, as they were proud of being citizens of Praeneste.

Praeneste was only fully integrated into Roman society around the beginning of the 1st century BC. At that time, Rome was fighting the Social War, and was forced to make concessions to its allies in exchange for their support. Therefore, after 90 BC, the inhabitants of Praeneste received Roman citizenship, and the town became a municipium. Praeneste played an important role during the civil wars between Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla. The town was controlled by the Marians until 82 BC, when it was taken by Sulla’s forces after a siege. The town and its inhabitants were severely punished by the victors. The male inhabitants of Praeneste were massacred without distinction, and the town was looted. Additionally, the town’s fortifications were dismantled, a colony of Sulla’s veterans established, and the remaining townspeople moved from the hill to the plain beneath.

Praeneste never fully regained its importance and prosperity after its capture by Sulla. Nevertheless, during the Roman Empire, it had become reputed as a favorite summer resort of wealthy Romans, and a pleasant place for suburban retirement. Augustus, for instance, is said to have frequented Praeneste, while his successor, Tiberius, once recovered from a dangerous attack of illness there. Hadrian built a large villa in Praeneste, and Marcus Aurelius was residing in the town when his seven-year-old son, Marcus Annius Verus, died. Praeneste was also the favorite place of retirement of the poet Horace, and Pliny the Younger, best-known for his letters that have survived till this day.

Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia: Temple of Birth History

Praeneste’s greatest claim to fame, however, was the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia. The date of the temple complex is still a subject of debate. In general, the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia is believed to have been built towards the end of the 2 nd century BC, perhaps around 120 BC. Some scholars, however, believe that the temple was constructed several decades earlier, i.e. around the middle of the 2 nd century BC. Additionally, the archaeological evidence indicates that there was already a cult to Fortuna Primigenia as early as the 4th century BC, long before the temple was constructed.

It has been suggested that because there was a need for a place of worship dedicated to the goddess, the temple was eventually built. Alternatively, it has been hypothesized that the local aristocrats, who had grown wealthy thanks to trade with the East, decided to build the temple for this goddess.

The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia was built into the side of a hill. Due to its prominent location, the sanctuary could be seen from all over Latium, perhaps even from Rome. The temple complex consists of multiple levels of terraces and staircases, a basilica, and a curia. In addition, the temple complex also included two reservoirs, which not only supplied water to a great fountain, but also to the town. At the top of the sanctuary was a small circular temple to the goddess. The sanctuary rose to a height 137.2 m (450 ft.), and its base had a width of over 396.2 m (1300 ft.).

It has been claimed that the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia was one of the largest, if not the largest, temples in ancient Italy. On the oldest level of the sanctuary, i.e. the basilica, there are two small grottoes, or caves. The western grotto is thought to be the site where the original goddess shrine was built. The temple complex was subsequently built up around this shrine.

Fortuna Primigenia Was A Powerful Early Roman Oracle Cult

Praeneste’s Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia was renowned for its oracular cult, and an account of it can be found in Cicero’s On Divination . In this work, Cicero reports that the divination performed by the sanctuary’s oracle was based on the method of sortes, i.e. the drawing of lots, and that the lots were discovered by a man named Numerius Suffustius:

“According to the annals of Praeneste, Numerius Suffustius, who was a distinguished man of noble birth, was admonished by dreams, often repeated, and finally even by threats, to split open a flint rock which was lying in a designated place. Frightened by the visions and disregarding the jeers of his fellow-townsmen he set about doing as he had been directed. And so when he had broken open the stone, the lots sprang forth carved on oak, in ancient characters.”

Cicero continues by reporting that when the lots were discovered, there was an olive tree overflowing with honey on the spot where the sanctuary was later built. The wood from the tree was used to make a chest, in which the lots were kept:

“There is a tradition that, concurrently with the finding of the lots and in the spot where the temple of Fortune now stands, honey flowed from an olive-tree. Now the soothsayers, who had declared that those lots would enjoy an unrivalled reputation, gave orders that a chest should be made from the tree and lots placed in the chest. At the present time the lots are taken from their receptacle if Fortune directs.”

Cicero is skeptical about divination by lots (as well as other forms of divination), and asserts that only the common people were inclined to believe in the oracle’s ability to do so:

“What reliance, pray, can you put in these lots, which at Fortune's nod are shuffled and drawn by the hand of a child? And how did they ever get in that rock? Who cut down the oak-tree? and who fashioned and carved the lots? … This sort of divining, however, has now been discarded by general usage. The beauty and age of the temple still preserve the name of the lots of Praeneste — that is, among the common people, for no magistrate and no man of any reputation ever consults them;”

In spite of Cicero’s skepticism, the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia and its oracle continued to flourish. In fact, the temple complex was only shut down during the second half of the 4th century AD. In 380 AD, the Edict of Thessalonica was issued, which made Nicene Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire. This meant that paganism was no longer tolerated, and the Sanctuary of Fortune Primigenia was forced to close.

The Fate of Fortuna’s Sanctuary

Unlike some other Roman temples, for example, the Pantheon, the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia was not converted into a Christian church. Neither was it destroyed. Instead, it was simply abandoned, and fell into ruin. During the Middle Ages, the modern town of Palestrina was gradually built over the remains of the massive temple complex.

Palestrina’s Palazzo Colonna Barberini, named after the two noble families that ruled over Palestrina, is one of the largest structures built on the old shrine complex. The Colonna family turned the town into their personal fief during the 11th century, while the Barberinis purchased the town later on, i.e. around 1630. Today, the Renaissance palazzo is owned by the Italian state, and, since 1953, houses the National Archaeological Museum of Palestrina.

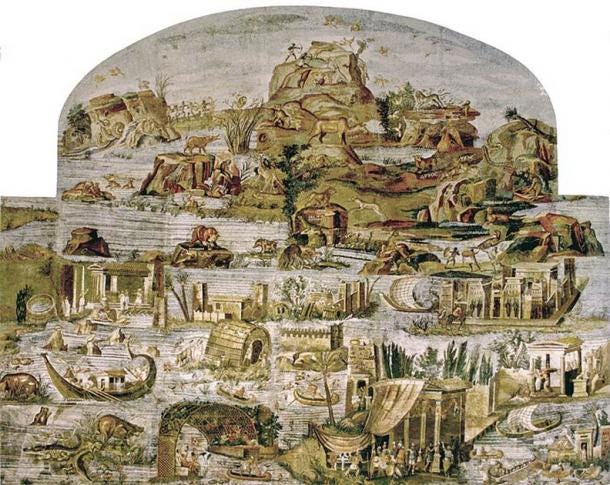

One of the most impressive exhibits in the museum is the so-called Nile Mosaic. This is a work of art that vividly depicts a Nilotic scene with various figures, including real and imagined animals, Egyptian priests performing rituals in their temples, Ethiopian hunters, and Ptolemaic Greeks. It is estimated that over half a million tesserae (mosaic tiles) were used to make the mosaic. Some of these tesserae are extremely small, measuring just a few millimeters (one millimeter is 0.04 inches) in diameter. By using such tiny tesserae, the makers of the Nile Mosaic were able to produce incredibly detailed images.

The mosaic dates to the 1st century BC, and is considered to be one of the most impressive mosaics of the late Hellenistic period. Scholars are of the opinion that it was made by Alexandrian craftsmen. The mosaic was never part of the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primiginia, but believed to have once covered the floor of a nymphaeum.

During the Middle Ages, the Nile Mosaic remained in its original location but was mostly forgotten. It later reappeared in historical records towards the end of the 16th century. During the 1620s, the cardinal-bishop of Palestrina, Andrea Baroni Peretti Montalto, had the mosaic removed from the floor, and sawn into 20 pieces, so that it could be transported to Rome for restoration. While in Rome, the Nile Mosaic was acquired by Francesco Barberini, another cardinal, and a great collector of art. Ten years after the Barberinis bought Palestrina, the mosaic was returned to the town. Unfortunately, the cart that was carrying the mosaic was involved in an accident, which caused the pieces to be damaged. After another round of restoration, the Nile Mosaic returned to Palestrina, and found a new home in the Palazzo Colonna Barberini.

The Palazzo Colonna Barberini is fortunate to have survived the Allied bombings during the Second World War. The rest of the town, however, was not so fortunate, and many of the houses that were built on the top three terraces of the ancient sanctuary were reduced to rubble. Incidentally, as a precaution, the Nile Mosaic was kept at the Museo Nazionale Romano in Rome during the war to protect it. The bombing of Palestrina, however, was a stroke of good luck for the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia, as it led to its rediscovery. Once the rubble was cleared, the ancient temple complex was visible once more.

In the years after the Second World War, the ruins of the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia were turned into an archaeological park, whereas the Palazzo Colonna Barberini, as mentioned earlier, was converted into a museum. In addition to the Nile Mosaic, the museum also displays other archaeological finds from ancient Praeneste, frescoes from the Renaissance, and a scale model of the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia.

Features of the ancient Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia have inspired Italian architects over the ages. The Victor Emmanuel II National Monument on Rome’s Piazza Venezia, for instance, is reminiscent of the temple complex’s overall design.

Top image: Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia Source: Enrico Rovelli / Adobe Stock

By Wu Mingren

References

Cicero, On Divination [Online]

[Falconer, W. A. (trans.), 1923. Cicero’s On Divination .]

Available at: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cicero/de_Divinatione/home.html

Dragstra, L., 2018. Palestrina: Ancient Praeneste (part 1). [Online]

Available at: https://corvinus.nl/2018/12/18/palestrina-ancient-praeneste-part-1/

Dragstra, L., 2018. Palestrina: The Nile Mosaic. [Online]

Available at: https://corvinus.nl/2018/12/22/palestrina-the-nile-mosaic/

LatiumMirabile, 2020. Nile Mosaic of Palestrina. [Online]

Available at: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/nile-mosaic-of-palestrina

LatiumMirabile, 2020. Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia. [Online]

Available at: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/sanctuary-of-fortuna-primigenia

Piperno, R., 2020. Palestrina: Fortuna Primigenia Shrine. [Online]

Available at: https://www.romeartlover.it/Palestrina2.html

Rome Hints, 2020. The Surroundings of Rome: The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in Palestrina, Destination of Believers from All over the Roman World. [Online]

Available at: https://www.romehints.com/en/The-surroundings-of-Rome-the-Sanctuary-of-Fortuna-Primigenia-in-Palestrina-destination-of-believers-from-all-over-the-Roman-world/

Smith, W., 1854. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography: Praeneste. [Online]

Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0064:entry=praeneste-geo

Thalia Took, 2013. Frotuna Primigenia. [Online]

Available at: http://www.thaliatook.com/OGOD/primigenia.php

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010. Praeneste. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Praeneste