Ancient Pattern Poetry – A Visual Story

Pattern poetry (known variously as figure poem, shaped verse, visual poetry, concrete poetry, and carmen figuratum) is a form of poetry that may be easily recognized due to the arrangement of its lines in an unusual configuration. Pattern poetry combined visual and literary elements, the former serving to convey and enhance the emotional content of the latter.

Pattern poetry is known to have existed in the West as early as the Hellenistic period and continues to be in use even today. Pattern poetry existed in other world cultures as well, though they may be quite different from their Western counterparts.

In Europe, the earliest known examples of pattern poetry date to the Hellenistic period , i.e. around the end of the 4th century BC. It may be mentioned, however, that in the Heraklion Museum in Crete, there is the so-called ‘ Phaistos disk ’, which is a grey clay disk with a spiral text imprinted on it. The disk is tentatively dated to 1700 BC and may be the oldest example of pattern poetry.

Unfortunately, the text is in Minoan A , which has not been deciphered, and we therefore do not know the nature of the inscribed text . Returning to the Hellenistic period, there are six surviving patterns that can be authenticated. Three of these were said to be written by Simmias of Rhodes, while Theocritus, Dosiadis of Crete, and Vestinus are each attributed with the authorship of one poem.

The Pattern Poetry of the Hellenistic Period

Of the six poems, those written by Simmias of Rhodes are the oldest, as he flourished around 325 BC, earlier than the other three poets. Two of Simmias’ poems, the Axe and the Wings , are thought to have been inscribed on votive objects, the former on a votive copy of the axe (preserved in the Temple of Athena ) purported to have been used by Epeius to make the Trojan Horse , and the latter on the wings of a statue representing Love as a bearded child. The last poem, known as the Egg , is believed to have been inscribed on an egg and unlike the other two poems was a tour-de-force that served to display the poet’s skill.

The last known Hellenistic pattern poem was written by Vestinus (known also as Besantinus) who lived during the 2nd century AD. In an inscription, Vestinus (whose full name was L. Julius Vestinus) is described as “High-priest of Alexandria and all Egypt, Curator of the Museum, Keeper of the Libraries of both Greek and Roman at Rome, Supervisor of the Education of Hadrian, and Secretary to the same Emperor”.

Vestinus is credited with the authorship of the Altar of the Muse . Due to certain similarities with Dosiadis’ Jason’s Altar , some scholars are of the opinion that the Altar of the Muse was written by Dosiadis instead. In the centuries after Vestinus, it is unknown if Greek pattern poetry was being written.

It is possible that this type of poetry was written but did not survive till the present day. We only hear of the re-emergence of Greek pattern poetry in the 7th century AD. A hymn from around 625 AD written by Acarthistos is rumored to have been a pattern poem, though its existence cannot be confirmed today.

While Greek pattern poetry ‘disappeared’ between the 2nd and 7th centuries AD, there are examples from this period for Latin pattern poetry. Two poets are known by name – Laevius and Optation, who lived during the 1st and 4th centuries AD. Apart from these two, the other Latin pattern poets were anonymous.

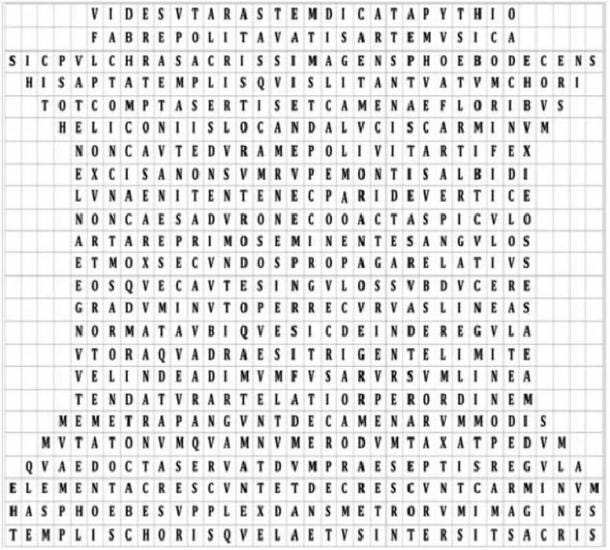

One of the best-known Latin pattern poems from this period is the Enigma of Sator , known also as the Sator Square . Unlike the Greek pattern poems, the Enigma of Sator is neither a poem (it was used, in fact, as a talisman) nor did it have a particular visual emphasis.

Nevertheless, the Enigma of Sator has been printed as a pattern poem so many times over the centuries that it is now considered to be an essential piece in pattern poetry literature. Examples of this word square have been found in the ruins of Pompeii (1st century AD) and it continued to be in use as late as the 19th century.

For those unfamiliar with the Enigma of Sator , it is a 5 x 5 word square containing the words ‘sator’, ‘arepo’, ‘tenet’, ‘opera’, and ‘rotas’, which can be read the same horizontally, vertically, and backwards. The Enigma of Sator can be interpreted in a variety of ways. It is, for instance, most commonly used as a protective talisman against diseases and disasters.

Another interpretation is that the words of the square formed a phrase, which have been variously translated as “The sower Arepo holds the wheels with effort”, “The sower Arepo leads with his hand, i.e. work the wheels, i.e. plough”, and “The Great Sower holds in his hands all works”. Some have also pointed out that the word ‘tenet’ in the middle (both horizontally and vertically) is a palindrome and forms a cross.

Although the Roman Empire ended in the 5th century AD, Latin continued to be used in Europe during the medieval period. During the Early Middle Ages , monasteries were not merely religious centers but also centers of scholarship and learning. Thus, Latin pattern poetry from this period is traditionally listed by the name of the monasteries that the manuscripts are associated with.

Nevertheless, many writers of pattern poetry are known by name and hailed from all parts of Europe. These include Alcuin of York (an Englishman who served as Charlemagne’s mentor), the French philosopher, Peter Abelard (a wheel-shaped poem is attributed to him), and Florencius / Florencio, a Spanish monk from the Monastery of Valeranica.

Pattern Poetry of Germany

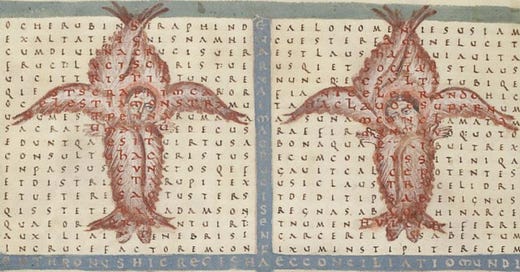

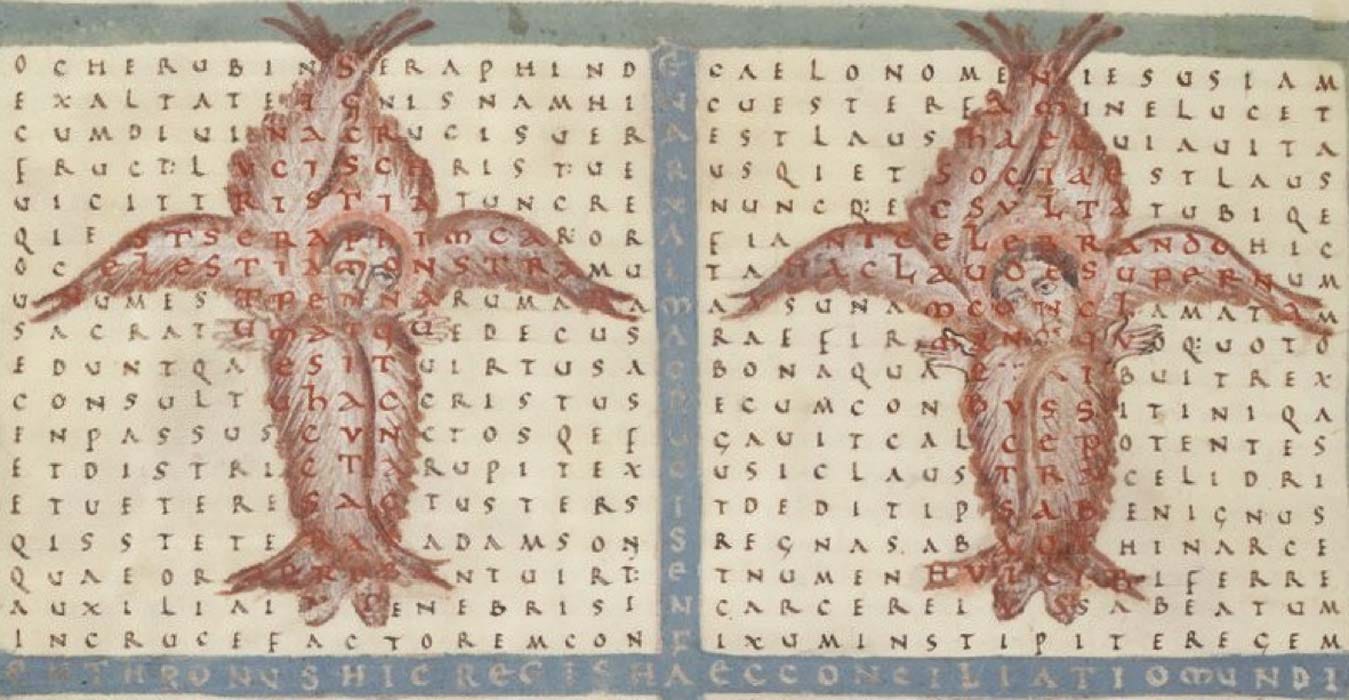

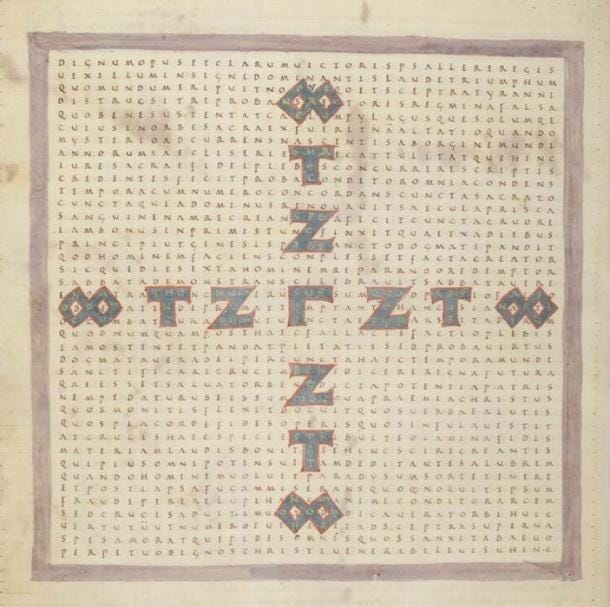

Arguably the most prolific pattern poet of this time, however, was Saint Rabanus Maurus (also called Hrabanus Magnentius). Dick Higgins, in his book, Pattern Poetry: Guide to an Unknown Literature , gives a list of 32 pattern poems written by Rabanus, 30 of which are carmina cancellate (gridded poems), and the other two carmina figurata (figured poems).

Rabanus was born around 780 AD in Mainz, Franconia (a region in modern Germany), and died in 856 AD in Winkel, Hesse (also in modern Germany). Rabanus was a scholar whose works contributed immensely to the development of German language and literature, hence earning him the title Praeceptor Germaniae, meaning ‘Teacher of Germany’. In addition to that, Rabanus served as the master of the monastic school of the Abbey of Fulda (in Hesse), later becoming the abbot of the said abbey, and later still, the archbishop of Mainz.

As one might expect from a man of the cloth, the majority of Rabanus’ pattern poems dealt with religious, specifically Christian, themes. As an example, poem number 5 in Higgin’s list is “a square text on angels, with letters forming the inscription "crux salvus" and the name of some celestial being on each of these letters”, whereas number 21 reads “a square text with five Xs arranged in a cross, telling of the significance of the Holy Sacraments”.

One of Rabanus’ pattern poems, however, deals with a secular theme. Poem number 1 depicts a heroic figure of Ludwig (also known as Louis) the Pious, Charlemagne’s successor as Holy Roman Emperor and the dedicatee of that particular poem. Interestingly, the pattern poems were not drawn by Rabanus himself, but were made by the master scribes working in the abbey’s scriptorium.

Although Latin was the language of scholarship in Europe up until the 18th century, pattern poetry was also written in other European languages, especially from the Renaissance onwards. In the Italian language, for instance, pattern poetry was written by such poets as Nicolò de’ Rossi and Guido Casoni. de Rossi’, who lived between the 13th and 14th centuries, is thought to have written the earliest pattern poems in any modern European language.

According to de’ Rossi’s manuscript notes, one of his poems, Canzona 247 is supposed to have the shape of a stella (meaning ‘ star’), whereas another, Canzona 248 , has the shape of a cathedra, (meaning ‘arch’). The shape of both poems, by the way, do not really match the de’ Rossi’s description.

Casoni, on the other hand, lived between the 16th and 17th centuries, and is known to have written 12 pattern poems. The shapes of his poems include a column, a pair of whips, a cross, and three nails, all of which are clearly associated with the Passion of Jesus Christ.

Other European Pattern Poetry

One of the best-known pattern poems written in the French language is attributed to François Rabelais , who lived between the 15th and 16th centuries. A bottle and cork shaped poem is found in Book V of his famous work, Gargantua and Pantagruel . As this book was published years after Rabelais’ death, and its contents of a lower quality than the previous books, scholars doubt that it was actually written by him.

Other Frenchmen who wrote pattern poetry include Estorg de Beaulieu and Jean de Boyssières, whose poems had religion as their theme. In the English language, there are about 110 known pattern poems that were written before 1750. The poems from England have been noticed to be quite conservative, the majority of them imitate the shapes of the ancient Greek ones.

On the other hand, the Scottish and Welsh poems have more unique shapes. Some examples of English-language pattern poets include Robert Baron, who wrote three pattern poems (one in the shape of an altar and two wedge-shaped ones), Matthew Stevenson, who wrote a set of three lozenge-shaped poems, and Thomas Watson, said to have written the earliest pattern poem in English (if Scottish poems are excluded).

Pattern Poetry of the East

Pattern poetry was not unique to European literature and may be found in other non-European languages around the world. Pattern poems can be found in Chinese literature , with one theory going so far as to say that pattern poetry originated in the East. An example of a highly sophisticated Chinese pattern poem is Su Hui’s Xuanji Tu (translated literally as Picture of the Turning Sphere , but more commonly known in English as Star Gauge ).

Su Hui was a female poet who lived during the 4th century AD and whose works are reputed to have numbered in the thousands. Sadly, the Xuanji Tu is the only one known to have survived. The story behind the Xuanji Tu is as follows: Su Hui was married to the governor of Gansu province. It was common for men of such status to have concubines and Su Hui’s husband was no exception.

Su Hui was unhappy with this, and when her husband was relocated to a faraway area, the poet refused to go with him. His concubine, however, was happy to go along. As a result, Su Hui was cut off completely from her husband, and in her grief, wrote, more precisely, wove onto brocade, the Xuanji Tu for him. Upon reading his wife’s poem, Su Hui’s husband left his concubine and returned to her.

The Xuanji Tu is a complex piece of work and is a palindrome poem. The poem is a 29 x 29 square, thus containing 841 Chinese characters. The outer border of the poem is meant to be read in a circle, while the characters within may be read in so many ways that up to 3,000 shorter poems may be produced. Examples of these verses (in English) include “so much so far away gone; it wounds affections deep”, and “a flame like ours, blazing up slowly, won’t stop burning; my worries gone deep, I lavish care on things yet to come”.

The Monk and the Poet: Meet the Rebels behind the Legendary “Journey to the West”

3,500-Year-Old Advanced Minoan Technology Was ‘Lost Art’ Not Seen Again Until 1950s

Lastly, some words may be said regarding the pattern poetry of India, which, like their Chinese counterparts, have not been so widely studied in the West. The majority of the Indian material falls into a group of forms known as citrakavyas. The main feature of this type of poem is that it (or a section of the poem) is presented stanzaically on one side, while the same poem, or another section of it, is presented visually on another.

These visual representations are known as bandhas, which have been divided into nine forms by William Yates – the crisscross (supposedly a representation of the falling urine of a cow), the drum, the simple wheel, the great / potter’s wheel, the lotus, the sword, the bow, the necklace, and the pyramid / tree / other complex form. The citrakavyas are found not only in Sanskrit literature, but also in other languages from India, including Hindi, Marathi, and Tamil.

Top image: Rabanus’ pattern poem a square text on angels. (Goodbichon / Public Domain )

By Wu Mingren

References

A Research Guide. 2019. What are the Visual Patterns Used in Poetry – A Simple Introductory Guide . [Online] Available at: https://www.aresearchguide.com/visual-patterns-in-poetry.html

Atsma, A. 2017. Pattern Poems . [Online] Available at: https://www.theoi.com/Text/PatternPoems.html

Dubois, M. 2013. Su Hui: The Palindrome Poet. [Online] Available at: https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2013/04/su-hui-the-palindrome-poet/

Higgins, D. 1987. Pattern Poetry: Guide to an Unknown Literature . State University of New York Press.

Hinton, D. 2019. Su Hui Translation . [Online] Available at: https://www.davidhinton.net/su-hui-high-res

Loyola Press. 2019. Saint Rabanus Maurus . [Online] Available at: https://www.loyolapress.com/our-catholic-faith/saints/saints-stories-for...

Ott, M. 1911. Blessed Maurus Magnentius Rabanus . [Online] Available at: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12617a.htm

Solt, M. 1968. Concrete Poetry: A World View . [Online] Available at: http://www.ubu.com/papers/solt/

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2013. Magic Square . [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/magic-square

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Pattern poetry . [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/pattern-poetry

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2019. Rabanus Maurus . [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rabanus-Maurus

The Public Domain Review. 2019. Medieval Pattern Poems of Rabanus Maurus (9th Century) . [Online] Available at: https://publicdomainreview.org/collections/medieval-pattern-poems-of-rab...

www.taliscope.com. 2019. The Sator Magic Square . [Online] Available at: http://www.taliscope.com/Sator_en.html